How I Met Him

How I Met HimR J Cooper DFC - Jack Cooper

A Few Glimpses into His Short Life

You can access a PDF version for easy printing and reading Here

Who Was R J Cooper?

Ronald Jack Cooper was a country boy from a farm in the locality of Eurongilly not far from Junee in the Riverina district of the State of New South Wales. At aged 20 in 1939 he joined the (British) Royal Air Force (RAF). At age 22, as a pilot of a Vickers Wellington bomber, he was lost in action over North Africa.

How I Met Him

How I Met Him

My first meeting with R J Cooper was a very brief encounter. It was only some time later that this brief encounter took on a life of its own.

In February 2016, I was returning from a family visit in Wagga Wagga in the Riverina. It’s a trip I’d done a few times so decided to find some Riverina back roads through the farmlands to make the ride a bit more interesting. I was on a minor sealed road heading north-east from Wagga Wagga when I spotted a small, somewhat unkempt memorial. Being curious, I stopped and explored.

A nearby sign identified the locality as Eurongilly. And that’s all it is – a locality. There’s no village as such, although there is a bush fire brigade shed. I subsequently discovered that Eurongilly also has a public school but I didn’t see it on that visit.

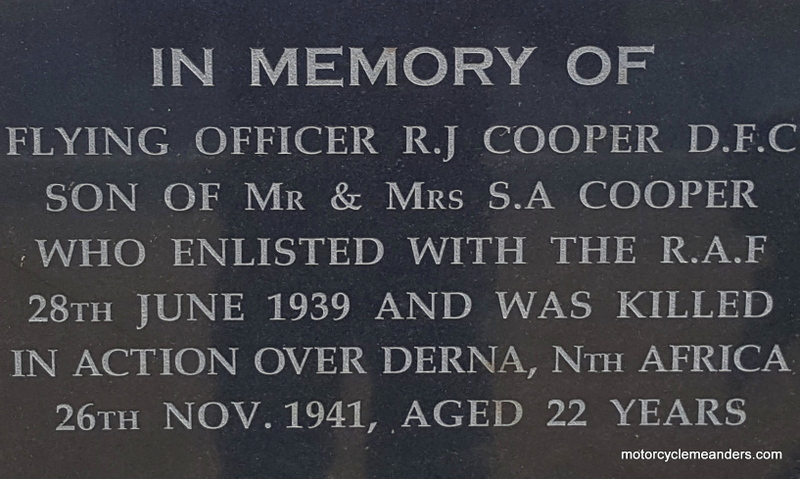

On the verge of the road were four brick pillars supporting white wrought iron gates. The two centre wider gates bore a wrought iron inscription that announced that it’s the “R J Cooper Memorial”. One of the pillars had a plaque that read:

IN MEMORY OF

Flying Officer R J Cooper DFC, son of Mr and Mrs S A Cooper, who enlisted with the RAF 28th June 1939 and was killed in action over Derna, Nth Africa 26th Nov 1941, aged 22 years.

Behind the pillars and wrought iron gates, drought-dried long grass camouflaged what seemed to have been a play park of sorts. A children’s merry-go-round languished at the far end. A heavily over-grown tennis court sat forlornly alongside the park. It looked a lonely, desolate sight that so suited the impact that was fast taking effect as I read the plaque over and over again.

Behind the pillars and wrought iron gates, drought-dried long grass camouflaged what seemed to have been a play park of sorts. A children’s merry-go-round languished at the far end. A heavily over-grown tennis court sat forlornly alongside the park. It looked a lonely, desolate sight that so suited the impact that was fast taking effect as I read the plaque over and over again.

Without knowing what R J Cooper looked like, he was already becoming an image in my mind. A young man used to outdoor farm life, a hard-worker, suntanned, a weather-beaten hat sitting awry on his head and his baggy work pants dragging in the dry dirt; just like the several photos I have seen of cousins of a similar age who lived in similar circumstances.

But there was a big difference in the case of R J Cooper. From the farmlands of Eurongilly, his short life took an exciting turn. He joined the RAF. But not much more than two years later, he met a lonely death in the dark (as I would later discover) somewhere high over the Libyan coastal town of Derna. I wondered how he ended up so far away from his home in Eurongilly.

Slowly, I began to take in the other plaques on the pillars. The centrepiece of the memorial was obviously R J Cooper; and it seemed to have been the creation of devoted parents. In fact, as I would learn, it was the initiative of the Eurongilly-Mitta Mitta Patriotic Association (lingering from war-time fervour but now long defunct). The other plaques honouring Eurongilly locals in World War II and the Vietnam War revealed not only the broad extent of local involvement but also the depth of the Coopers’ contribution, with four names from World War II (all brothers) and one from Vietnam (a son and nephew of the brothers).

Discovering his Life

It was several weeks later that I realised a part of me hankered to discover who R J Cooper was and how and why he ended up over Derna on that fateful night.

My first bit of tangible evidence about him came from a search of the Australian War Memorial site. That gave me his full name for the first time: Ronald Jack Cooper. Also his service number and unit: 43281, No. 38 Squadron (RAF).

In the collection of the Junee Historical Society and Junee Broadway Museum there was a hand-written life of the Cooper family by Ronald Cooper’s brother (undated but obviously written many years ago). It revealed something of his early life and that he was called Jack rather than Ronald or Ron.

Slowly, I came to piece together more of his short life.

This is the story of Jack Cooper.

Jack in Eurongilly

Jack grew up on his parents’ farm in the district of Eurongilly. His grandparents had settled there at a time when they had to clear the land by hand; and start from scratch with sheep and later with wheat. Jack was the second youngest of six children – five boys and one girl.

Jack’s primary school, as with his siblings, was at the Eurongilly Public School, which I found and visited on a subsequent trip; and told the school kids about Jack Cooper. The school is located at the corner of the original Cooper property on a piece of land donated by Jack’s father.

Jack's high school education was undertaken as a boarder at the Yanco Agricultural High School in Yanco, a small town in the Riverina area of south-western NSW. He attended Yanco from 1933 to 1937, finishing with his NSW Leaving Certificate. He enrolled at the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Veterinary Science, where he spent 1938. He dropped out at the end of the year and returned to his parents’ Eurongilly farm where he spent the first half of 1939.

It wasn’t long into 1939 before he revealed his longer-term ambitions.

Introduction to the RAF

Early in 1939, Jack either spotted or was made aware of an advertisement in newspapers:

Gentlemen of the Dominions, Colonies and Territories under the Crown are invited to apply for Short Service Commissions in His Majesty’s Air Force..…Apply to RAAF H.Q., Melbourne.

Such a process had been in place since 1927, although until 1938 the invitations had been directed at Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) officers who had graduated from the RAAF Officer Training School at Point Cook. This invitation of early 1939 might have been the first and – because of the declaration of war later in the year – certainly the last one inviting applications from young men who may have had no flying training at all.

Hundreds applied, but only twenty-two applicants were accepted. Jack was one of those twenty-two. Their letters of acceptance, dated 5 June 1939, directed them to embark on RMS Orama; and report at the flying training school (in Britain) on 26 September 1939.

Journey to Britain

In Brisbane on 31 July 1939, RMS Orama began its collection of these aspiring RAF pilots. Jack and eight others of the twenty-two boarded the Orama in Sydney on 12 August 1939. From there, the Orama continued its mission to Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle, from where, with all twenty-two now together, it steamed into the Indian Ocean on 21 August 1939.

In Brisbane on 31 July 1939, RMS Orama began its collection of these aspiring RAF pilots. Jack and eight others of the twenty-two boarded the Orama in Sydney on 12 August 1939. From there, the Orama continued its mission to Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle, from where, with all twenty-two now together, it steamed into the Indian Ocean on 21 August 1939.

Their voyage to Britain took them first to Colombo, the capital of Ceylon – today’s Sri Lanka. As they re-boarded after some sight-seeing in Colombo, their excitement was soon replaced by more sobering news of a change of route. It was deemed no longer safe to continue to the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean Sea. The ship would be re-routed to the east coast of Africa, Mombasa (Kenya) and round the Cape of Good Hope, calling into Cape Town (South Africa) and up the west coast to Freetown (Sierra Leone).

Between Colombo and Mombasa, they learned that Britain and its Commonwealth allies had declared war on Germany. Their circumstances and their mood suddenly changed from expectant to apprehensive.

The voyage continued round the Cape and onto the West African port of Freetown. Arriving there was confronting: their first exposure to the reality of war. Freetown, the capital of the British West African colony of Sierra Leone, was central to the Allies’ strategy during World War II. It served as a convoy station, with up to 200 cargo and military vessels moving in and out of its well-protected harbour at the height of wartime activities. Already war ships were anchored there; and more were steaming towards it from Gibraltar.

RMS Orama eventually docked in Southampton on Friday 13 October 1939 – some three weeks after the originally scheduled date of arrival and over two weeks after their date for reporting to the flying training school.

RAF Training

The group of twenty-two, by now closely bonded, with even closer friendships forming amongst individuals within the group, stayed together for their early training. The day after their arrival, on 14 October 1939, they presented themselves at the Air Ministry to report for duty.

Cambridge

The next day they began their first posting at No.1 Initial Training Wing at Cambridge. Their two-week Cambridge posting was all about being introduced to the Air Force and, seemingly, some basic revision of the 3Rs.

Ansty

It was good news for Jack and the others to be told that on 30 October 1939 they were off to No.9 Elementary Flying Training School in Ansty near Coventry in the British Midlands. Here Jack was taught the basics of flying and learned how to fly Tiger Moths. was exciting for them all. This is where most of them had their first flying experience. Within a day or two, most were getting such a feel for the controls that they were taking them for short, straight and level runs. Over the following days, they were extending their skills into taxiing, climbing, gliding, stalling, medium turns and finally landings. The landings posed the biggest challenge for them.

It was good news for Jack and the others to be told that on 30 October 1939 they were off to No.9 Elementary Flying Training School in Ansty near Coventry in the British Midlands. Here Jack was taught the basics of flying and learned how to fly Tiger Moths. was exciting for them all. This is where most of them had their first flying experience. Within a day or two, most were getting such a feel for the controls that they were taking them for short, straight and level runs. Over the following days, they were extending their skills into taxiing, climbing, gliding, stalling, medium turns and finally landings. The landings posed the biggest challenge for them. Cranwell

From Ansty, the group proceeded to RAF Cranwell in Lincolnshire on 10 April 1940.

The RAF Base at Cranwell was and still is home to the Royal Air Force College which trains the RAF’s new officers. It is considered by some to be the spiritual home of the RAF.

This was their introduction to the Officers’ Mess and all the trappings of being a commissioned officer. It was at this stage of his RAF career that Jack received his short service commission as Acting Pilot Officer.

During the war, Cranwell was used as an advanced training unit. The focus for Jack and his colleagues was on all aspects of crewing aircraft in war-time. This included intensive instruction on navigation, the operation of all forms of communication equipment, the disassembling and reassembling of weaponry, the use of machine guns in flight and detailed knowledge of the mechanics and operation of planes. And, of course, advanced flying lessons and experience.

During the war, Cranwell was used as an advanced training unit. The focus for Jack and his colleagues was on all aspects of crewing aircraft in war-time. This included intensive instruction on navigation, the operation of all forms of communication equipment, the disassembling and reassembling of weaponry, the use of machine guns in flight and detailed knowledge of the mechanics and operation of planes. And, of course, advanced flying lessons and experience.

The next step up from the Tiger Moths was the Hawker Harts and Hawker Hinds. These were both biplanes, two-seaters, light bombers and, as the war broke out, both were being retired from active service into training roles. It was on one of these aircraft that Jack Burraston – he wasn’t the pilot – was killed in a training accident.

By the end of the Cranwell posting, Jack and his colleagues were well-equipped for any role on Britain’s war-time aircraft. The breadth of training would prove particularly valuable for those who would be assigned to bombers, with their considerably longer and more complex missions; and requirements for greater versatility of crew members.

While Jack’s colleagues from the twenty-two advanced from Cranwell to their designated squadrons and types of aircraft at the end of June 1940, Jack remained there for another two months. Jack hadn’t got away to a particularly auspicious start at Cranwell. Ten days after arriving, on 20 April 1940, he was getting off a bus on his way back from the city of Lincoln 22 km away from the base, when he was struck by a car. He ended up with concussion and spent three weeks in hospital followed by a couple of months banned from flying. This delayed his transition from Cranwell to his next posting.

No. 11 Operational Training Unit

On 7 September 1940, Jack was posted to No. 11 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RAF Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire, about 18km south-west of Cambridge. No. 11 OTU was part of RAF Bomber Command and was set up to train night bomber aircrew particularly on the Vickers Wellington twin engine bomber.

This posting marked Jack’s grading to Pilot Officer. It’s called a grading rather than promotion because Acting Pilot Officer and Pilot Officer were gradings within the same rank.

It was here that his flying advanced from the training aircraft to his designated operational aircraft, the Vickers Wellington, affectionately known to its crews as the ‘Whimpy.’

The Whimpy was considered too slow for daytime bombing raids. Its speciality was its ability to carry heavy payloads long distances; but it was operationally effective only under cover of night.

Apart from flying the Vickers Wellington at Bassingbourne, Jack learned about every aspect of its structure, mechanics, operations and flying idiosyncrasies.

While Jack was at No. 11 OTU his operational training took him on several flights over Germany and occupied Europe. He flew as a crew member at this stage – serving as navigator or radio operator. On some flights he would have been designated second pilot, although the Whimpy didn’t have a co-pilot as such; not even a second pilot seat. The designated second pilot (a luxury that not every Wellington crew enjoyed) might have flown the plane home after it left enemy-occupied territory, but in all other respects he would have been fully occupied at his allotted task.

The records from No. 11 OTU’s operations don’t record the names of the flight crews; only the pilots. It’s not known how many flights Jack made over Europe. Anecdotal evidence, coming from or via others of the twenty-two, suggests Jack “went on many operational sorties over Europe, sometimes spending eight hours in the air.” The unit’s records indicate the sorties were “nickel raids” – code for pamphlet dropping. These raids exposed crew-in-training to the reality of flying over enemy territory. Nickel raids, by their very nature, would have penetrated into Germany, making the raids no less dangerous than a bombing raid; evidenced by the number of losses on nickel raids.

Operational Posting: No. 38 Squadron RAF

Jack’s service record has him posted to No. 38 Squadron with effect from 29 October 1940 for ‘flying duties.’

Jack’s service record has him posted to No. 38 Squadron with effect from 29 October 1940 for ‘flying duties.’

No. 38 Squadron was one of the few RAF squadrons to use the Vickers Wellington from the beginning to the end of the Second World War.

At the time of Jack's posting to 38 Squadron, it was also part of Bomber Command. Jack arrived there, however, as the squadron was beginning its preparations for being moved to the Mediterranean theatre where it would be based in North Africa. Because of its preparations to move to the Middle East, 38 Squadron didn’t undertake any operational sorties during October or November.

Transferring 38 Squadron from Bomber Command in Britain to the Middle East was a response to the military intentions and might of the Axis Powers (Germany and Italy in this context) that were being displayed by them in the north African desert.

From Britain to Egypt

As part of the preparations for the move to the Middle East, the squadron was strengthened by bringing into it complete flying crews and by replacing ground crew declared unfit for overseas duties. No. 115 Squadron, amongst others, was “raided” to meet these needs. On 8 November 1940, a complete crew from 115 Squadron was posted to 38 Squadron that included Alan “Dutchy” Holland, one of Jack’s closest friends (along with Albert Tindall) from the twenty-two. Palling up with Dutchy in preparations for heading out on such an unpredictable adventure to the Middle East was a great comfort to both of them. They spent almost three weeks together in Marham before they flew out.

As part of the preparations for the move to the Middle East, the squadron was strengthened by bringing into it complete flying crews and by replacing ground crew declared unfit for overseas duties. No. 115 Squadron, amongst others, was “raided” to meet these needs. On 8 November 1940, a complete crew from 115 Squadron was posted to 38 Squadron that included Alan “Dutchy” Holland, one of Jack’s closest friends (along with Albert Tindall) from the twenty-two. Palling up with Dutchy in preparations for heading out on such an unpredictable adventure to the Middle East was a great comfort to both of them. They spent almost three weeks together in Marham before they flew out.

On 12 November 1940, with much fanfare and ceremony, the squadron’s personnel, apart from flying crews, set out on what would be an eventful journey by train and sea, with a few brushes with enemy harassment in the Mediterranean despite being escorted by several light cruisers and destroyers. It was the end of the month before they reached their destination at Fayid in Egypt.

The turn of the flight crews came on 22 November 1940. Over 22 and 23 November the 38 Squadron Wellingtons took off for Malta in two groups. Jack was part of the second group. The flights to Malta were uneventful. However, Jack’s group, 24 hours behind the first group, was delayed in Malta because of an air raid that put one their planes out of action. The rest arrived in Ismailia in Egypt on 25 November 1940 and met up with the first group.

Both Fayid and Ismailia were temporary bases being used by 38 Squadron until completion of the squadron’s permanent base at Shallufa. All three bases were within close proximity to one another at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez. The air contingent joined the land contingent at Fayid on 7 December 1940; and all the squadron moved to Shallufa on 18 December 1940.

The Western Desert Campaign

So why the change to strategies that had 38 Squadron move to Egypt? And what played out during Jack Cooper’s time there?

The new development was the Western Desert Campaign or the Desert War. The campaign began in September 1940 with the Italian invasion of Egypt from its long-occupied colony of Libya. Although there had been skirmishing along the Libyan-Egyptian border between Italian and British forces, the fall of France in 1940 and the strengthening of Italian forces presaged fiercer battles in North Africa. The ultimate goals were control of the Suez Canal and protection of the vital oil resources that flowed through it. Moreover, loss of the Suez would inevitably be followed by loss of other British ‘possessions’ and, from a British perspective, this would change the strategic and military situation in the Middle East and Europe even beyond the foreseeable future.

If Britain and its Allies were to remain viable in the Second World War, the Suez must be held by them. For this, additional British and Allied forces were urgent and essential in the campaigns against the Axis Powers.

The role of 38 Squadron, along with others, was to form a night bomber wing and engage in regular attacks on Italian ports along the North African coast in order to hamper the movement of supplies to the Italian forces in the Western Desert; and destroy their bases there.

The year that followed the squadron’s arrival in Egypt saw the British push west through Libya, the advance of Germany’s Afrika Korps under Rommel against Allied forces, the siege of Tobruk and the campaigns mounted by the Allies to raise the siege culminating in Operation Crusader that resulted in relieving Tobruk, recapturing Cyrenaica (East Libya) and capturing airfields that would prove crucial for future air cover.

The balance would later swing the other way in favour of the Axis Powers with the subsequent loss of Tobruk and Libyan territory won in 1940-1941 before the ultimate show-down and Allied victory at El Alamein towards the end of 1942.

No. 38 Squadron in Egypt

Although the squadron’s home bases were on the Gulf of Suez, the bombing raids were launched from “landing grounds”. These were makeshift air strips in the desert that also housed a supply of fuel and armaments. The photo of the Wellington bomber “G and crew, Fuka Satellite, January 1941” (p.14) was taken at one of these landing grounds: LG016, called “Fuka Satellite”. There were some 40-50 such landing grounds within a few hundred kilometres from the Libyan border.

Shallufa

The usual flight pattern was to make a day-time flight from Shallufa to a landing ground nearer the Egypt/Libyan border where the aircraft would be refuelled and bombs loaded in readiness for a late afternoon or evening take-off for the night’s bombing raid. The plane would then return to the Landing ground before proceeding to its base at Shallufa (or Fayid in the early days).

Before he was given his own captaincy, Jack flew as second pilot. The second pilot wasn’t a co-pilot as such. There was no co-pilot seat; only some sort of collapsible seat. The second pilot would be expected to take on any of the other crew roles as needed. As with his time in No. 11 OTU, he would have helped out with or took on any of the roles indicated in the illustration below. With a six-man crew – seemingly more often the case earlier in the war than later – someone might have manned the front turret gun, with the second pilot taking on navigation or bomb aiming. The second pilot might also have flown the plane home or, at least, once out of enemy firing range.

Jack’s first sortie was out of Fayid on 15 December 1940. He was second pilot to P/O (Pilot Officer) Day with whom he did many sorties. The target was the military HQ as well as stores and troops at Bardia. There were several Wellingtons in the group that took off that day. They started leaving Fayid from 9.30am and flew to LG60 (Landing Ground 60) about 200km from the border arriving between 11.00am and 1.00pm. They took off from there on their bombing mission between 9.00pm and 10.00pm. They first flew north across the Egyptian coast before turning west to follow the coastline to Bardia. This was the normal practice to reach Libyan targets. Although they encountered cloud in the early part of their flight, they had clear, bright moonlight over the target area; and made direct hits on all parts of their targets. They reported only light anti-aircraft activity that night. They were all safely back between 1.00am and 3.00am next morning.

Over the coming months, Jack continued as second pilot to P/O Day undertaking sorties along the Libyan coast to Bardia, Tobruk, Gazala, Bomba, Bengazi (sometimes focussing on the port and at other times on the old town of Berka or the aerodrome at Benina), Sirte, Tamet and Tripoli.

During this period, on one night in February 1941, Jack and his fellow crew members were part of a seven-plane bombing raid on airfields in the south of the Greek island of Rhodes.

In April 1941, Jack joined the crew of his colleague from the twenty-two, Jack Slatter, who had also been assigned to 38 Squadron. Slatter was already flying as captain of an aircraft. He had his private pilot’s licence when he joined the twenty-two and, because of Jack’s accident at Cranwell, had two-months operational experience over Jack.

In April 1941, Jack joined the crew of his colleague from the twenty-two, Jack Slatter, who had also been assigned to 38 Squadron. Slatter was already flying as captain of an aircraft. He had his private pilot’s licence when he joined the twenty-two and, because of Jack’s accident at Cranwell, had two-months operational experience over Jack.

Jack continued to fly as second pilot to P/O Slatter until he was given his captaincy. That happened in June 1941.

On 5 June 1941, Jack embarked on his first sortie as captain of his own aircraft and crew. That day would always stay in his memory as a special milestone. His mission was a bombing raid on Benghazi. With heavy cloud cover it was impossible for him or his crew to assess the extent of the damage they inflicted.

On 11 June 1941, Jack and his new crew were part of a multi-plane sortie to Rhodes again, this time bombing the airstrip of Calato near the town of Lindos on the north-east of the island. They took off from Shallufa at 8.00pm and had landed back therfe by 3.00am.

Jack, in his role as captain, undertook many more sorties hitting targets along the Libyan coast until August 1941 when he and his crew became part of a detachment of 38 Squadron to be posted to Luqa in Malta.

No. 38 Squadron in Egypt

Although the squadron’s home bases were on the Gulf of Suez, the bombing raids were launched from “landing grounds”. These were makeshift air strips in the desert that also housed a supply of fuel and armaments. The photo of the Wellington bomber “G and crew, Fuka Satellite, January 1941” was taken at one of these landing grounds: LG016, called “Fuka Satellite” (Jack is in centre of the picture). There were some 40-50 such strips within about 250km from the Libyan border.

Malta

Jack and his crew spent more than two months based in Malta.

The principal target from Malta was Tripoli. They made many night raids with the most frequent missions being to hit the “moles” – the breakwaters creating the harbour – and the wharves and store houses that were built on the quays at the shore ends of the moles.

There were two moles making the Tripoli harbour: the Spanish Mole encircling the north of the harbour and the Karamanli Mole to the east. (They are not called that anymore.) Nearly every mission target mentions the moles, the quays and the store houses. Bombing the moles was often a diversion to allow mine-laying aircraft safer access to the harbour. These were both Wellingtons and Swordfish aircraft

On the night of 19-20 September 1941, while on a raid to Tripoli bombing the Spanish Mole and Quay and the Karamanli Mole, Jack’s aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire which ignited one of the parachute flares carried in the bomb cells. The aircraft was set on fire. Jack, as captain, while continuing to manage the damaged plane, directed other members of the crew how best to get the fire extinguished. He then brought his aircraft and crew safely back to Malta. This feat is mentioned in his DFC citation.

During their posting to Malta, Jack and his crew also made sorties into Sicily bombing the aerodrome and shipping as well as harbour installations at Palermo in the north of the island.

Late on the night of 25 October 1941, along with eight other Wellingtons, Jack and his crew, with four passengers (all the aircraft had four ground crew passengers) took off from Malta touching down at Shallufa next morning. A further five aircraft had made the same trip the day before.

Back at Shallufa

Jack had some well-earned leave on his return from Malta; as did all the crews that had been part of the detachment. There are anecdotal stories that Jack and his friend Dutchy Holland had some good leave-breaks in Cairo, Alexandria and Suez. Some members of the desert squadrons have written about taking a plane to the beaches of Haifa in what was then Palestine for some time out. One report has Jack meeting up with his brother Tom who was in the Middle East with the 9th Division of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

Jack had some well-earned leave on his return from Malta; as did all the crews that had been part of the detachment. There are anecdotal stories that Jack and his friend Dutchy Holland had some good leave-breaks in Cairo, Alexandria and Suez. Some members of the desert squadrons have written about taking a plane to the beaches of Haifa in what was then Palestine for some time out. One report has Jack meeting up with his brother Tom who was in the Middle East with the 9th Division of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

Jack’s next operational sortie wasn’t until 16 November 1941 when his was one of twelve aircraft to head out from Shallufa to Landing Ground 09 (LG09) for a bombing raid on Gazala. Eleven returned safely to Shallufa next day. Jack’s aircraft, on its way back to LG09, about ten miles from another landing ground, Fuka Satellite west of LG09, lost its port engine. It simply cut out. When Jack attempted to bring the plane into Fuka Satellite, the starboard engine lost revolutions and the plane dramatically lost height. Jack had no option but to crash land his aircraft in the desert dunes. He succeeded in doing so without damage to the airframe or injury to the crew. The report on the operation stated, “this forced landing is considered an excellent effort.”

The operations record doesn’t say what happened after they crash landed. Most likely Jack and the crew either made their way to Fuka Satellite or were spotted crash-landing and picked up. While the frame of the plane wasn’t damaged, the undercarriage took a beating. Jack and his crew didn’t fly that plane again. It’s probably now long-buried under the ever-shifting sands of the Libyan desert.

On 24 November 1941, Jack and his crew, in a different plane (all Vickers Wellingtons, of course) did some training runs out of Shallufa. Whether they were testing a newly repaired plane or testing themselves after the ordeal of the crash landing is unknown.

Jack’s Last Flight

On 26 November 1941, Jack and his crew in their Vickers Wellington designated ‘Q’ Z8736 (a different plane again from the one flown on 24 November), along with eight other aircraft, took off from Shallufa around midday headed for LG09. Their target was “Derna buildings”. As they had done so often before, they landed at LG09 for a refuel and loading of bombs. They took off from LG09 at 5.00pm, flew north to cross the coast and then turned to port for the trek west along the coastline to Derna.

On 26 November 1941, Jack and his crew in their Vickers Wellington designated ‘Q’ Z8736 (a different plane again from the one flown on 24 November), along with eight other aircraft, took off from Shallufa around midday headed for LG09. Their target was “Derna buildings”. As they had done so often before, they landed at LG09 for a refuel and loading of bombs. They took off from LG09 at 5.00pm, flew north to cross the coast and then turned to port for the trek west along the coastline to Derna.

At about 8.45pm, a few miles short of Derna, Jack was quick to call on his radio operator to send an SOS back to Base. The plane was in serious trouble. There wasn’t time for the wireless operator to transmit any message beyond the SOS. The situation rapidly became desperate and the radio operator fastened the key of the Morse Code transmitter. The long, continuous note was picked up by Base and gave hope that the crew might have bailed out. Maybe they did.

Between 8.00am and 10.00am on 27 November 1941, eight aircraft returned to Shallufa from their bombing raid on Derna. Only one aircraft, ‘Q’ Z8736, failed to return from the operation. While hope continued that the crew might have survived it was not so. No more was heard from them. Other pilots from the contingent reported severe electrical storms in the area around Derna. Whether they played a part or anti-aircraft fire brought the plane down is something only Jack and his crew knew. Whatever happened, the jammed Morse suggests it happened very quickly.

The operational report listed the flight crew as: P/O. Cooper, Captain, Sgt. Wren,

P/O. Eastman, Sgts. Peaker, McNeil and McKhool.

While all the operational reports list Jack as P/O indicating the commissioned rank of Pilot Officer, he was actually promoted to the next rank higher of Flying Officer (F/O) on 7 September 1941. His promotion was gazetted on 4 November 1941. He was in Malta when promoted. Jack would have been informed. From what I’ve learnt about Jack’s personality, it would have been typical of him to keep it to himself. However, his senior officers would also have been informed. Maybe it was a matter of the compiler of the operational reports who hadn’t realised; and they weren’t being carefully checked at the time; not surprisingly in a war situation.

R J Cooper and the DFC

Sadly, Jack didn’t get to see the full extent of the North Africa Campaign’s successes in 1941. There was a lot more to come in the Campaign, including the subsequent loss of Tobruk before the final Allied victory at El Alamein; but the Wellington night raids during 1941 were crucial to the early Allied advances and victories, including breaking the Axis siege of Tobruk.

Sadly, Jack didn’t get to see the full extent of the North Africa Campaign’s successes in 1941. There was a lot more to come in the Campaign, including the subsequent loss of Tobruk before the final Allied victory at El Alamein; but the Wellington night raids during 1941 were crucial to the early Allied advances and victories, including breaking the Axis siege of Tobruk.

Jack was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). According to British Government guidelines, the DFC is awarded “in recognition of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy in the air.”

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded as one or other of two 'types' – Immediate, i.e. for a specific act of gallantry; or non-immediate, for a period of exemplary performance. Jack’s fell into the latter category. Even though the citation mentions a particular incident, it’s clear that the award reflects a sustained high standard of “exemplary gallantry” over more than a year of operations “against the enemy in the air.”

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded as one or other of two 'types' – Immediate, i.e. for a specific act of gallantry; or non-immediate, for a period of exemplary performance. Jack’s fell into the latter category. Even though the citation mentions a particular incident, it’s clear that the award reflects a sustained high standard of “exemplary gallantry” over more than a year of operations “against the enemy in the air.”

The award wasn’t gazetted until 16 March 1943. The gazette entry announced the DFC was awarded “with effect from 28th October 1941.” The back-dating of the award would seem to have been a technique to step around the technicality that the DFC, as with most awards, at that time, could not be granted posthumously.

The original recommendation was sent from RAF HQ Middle East on 22 December 1941. The recommendation limited its scope to Jack’s time in 38 Squadron from October 1940 and specified that he had carried out 39 operational sorties totalling 312 operational flying hours. The key element in recommending the award were the words: “he has always carried out the task allotted to him with calm determination and energy…This officer’s activities...have all been of a high standard and well deserve recognition.” The recommendation mentions the incident of 19-20 September (described under the sub-heading “Malta” above) and states “his fortitude on the night of 19/20 Sept...is typical of his cool courage and devotion to duty.” The recommendation also specifies that the aircraft was flown back to Malta.

The citation was truncated to the words below (omitting squadron number, number of operational sorties and hours, and location of the base). In one respect, the scope is broadened by implicitly including time in No.11 OTU (he wasn’t posted to 23rd Squadron until the end of October 1940)..

Since October 1940, this officer has carried out many operational sorties. He has at all times displayed great coolness and determination in the execution of the tasks allotted to him. One night in September 1941, during a raid on Tripoli, his aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire which ignited one of the parachute flares in his aircraft. The aircraft caught fire, but, under Flying Officer Cooper’s direction, the flames were extinguished and the aircraft was flown safely back to base.

Jack’s parents saw four of their sons go off to the Second World War. Jack was the youngest of them. He was the only one who didn’t come home. The recognition given to him by the Distinguished Flying Cross was to be a treasured memory of him. His father received the award from the Governor General at Admiralty House in Sydney on 16 June 1944. His mother displayed the award on her dressing table where she looked at it every day for 39 years until she died in 1983 aged 98.

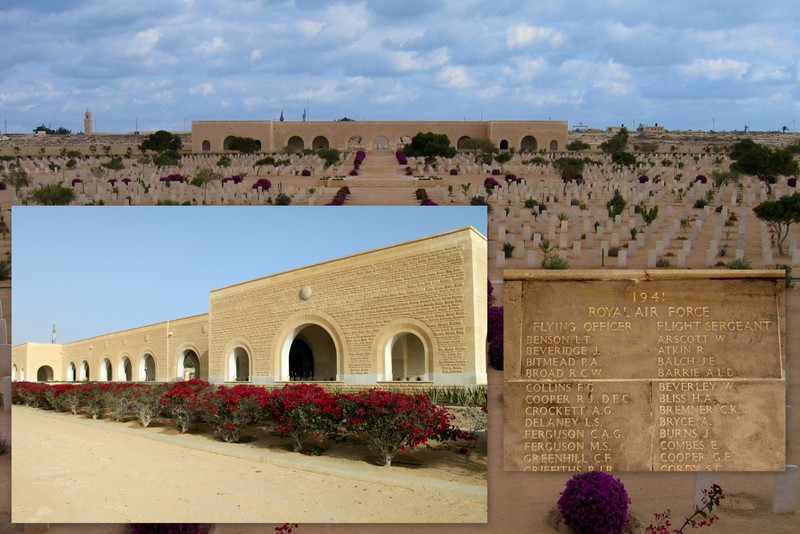

Alamein Memorial

Alamein Memorial

There has never been any trace of Jack’s plane or any of his crew. There is no grave to mark his or his crew’s last resting place. It’s somewhere in the Mediterranean Sea off the Libyan coast from Derna.

The Alamein Memorial, which is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission war memorial, was constructed to provide a permanent commemoration to those missing in action in The Desert War and adjacent geographical locations. The memorial is part of the El Alamein War Cemetery at El Alamein in Egypt.

The Air Forces panels at the memorial commemorate more than 3,000 airmen of the Commonwealth who died in the campaigns in North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and adjacent areas, who have no known grave.

R J Cooper DFC is one of the airmen commemorated there; along with all the members of his crew.

The Wellington Bomber

Perhaps a note on the Wellington Bomber might be a good finale to this story, given that the Wellington was so much part of Jack’s life and his final resting place.

Perhaps a note on the Wellington Bomber might be a good finale to this story, given that the Wellington was so much part of Jack’s life and his final resting place.

The Vickers Wellington served in the Mediterranean theatre from September 1940 until March 1945, remaining in use as a front-line bomber for that entire period.

The entry of Italy into the war in the northern summer of 1940 found the Desert Air Force very vulnerable. It had a small number of aircraft, mostly of obsolete or obsolescent types. The main bomber in use was the Blenheim. The Desert Air Force was strengthened by the Vickers Wellington.

The first Wellingtons reached No. 70 Squadron in Egypt in September 1940, replacing the Vickers Valentia, making the squadron a pure bomber unit. Squadron Nos. 37 and 38 arrived in Egypt in November already equipped with Wellingtons.

The Wellingtons played two roles in the desert war – direct attacks on Axis positions and supply dumps and attacks on the Axis supply route across the Mediterranean.

As the war in Africa turned in the Allies’ favour, the Wellington squadrons followed the retreating Germans west.

Remembering Jack

In addition to the R J Cooper Memorial at Eurongilly and the Alamein Memorial at El Alamein in Egypt, Jack’s name is commemorated on the Cenotaph in Junee and the Roll of Honour at Sydney University. His name is also inscribed on the Commemorative Roll at The Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Return to top of page Go to Fireside

| Site Map |