|

|

Al-Andalus March 2009

This trip preceded my Morocco tour. It covered Madrid, Toledo, Seville and Cordoba before making my way to Algeciras to catch a ferry across the Straits of Gibraltar to Tangier.

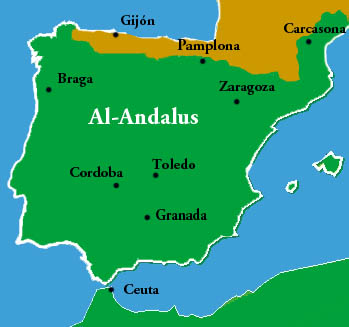

The title of this page – Al-Andalus – comes from the Arabic name given to a large part of central and southern Spain and Portugal that was governed by Muslims (Moors) between the 8th and 15th centuries. For the first half of this period, especially during the Caliphate of Cordoba in the 10th and 11th centuries, al-Andalus was considered a leading centre of learning, culture and economic activity throughout the known world. In succeeding centuries, al-Andalus became a province of the Berber (Moroccan-based) Muslim dynasties of the Almoravids and Almohads, subsequently fragmenting into a number of minor states, most notably the Emirate of Granada, which was the last of the Muslim states to hold out against the Christian kingdoms to the north. The surrender of the Emirate of Granada in 1492 meant the end of al-Andalus as a political entity. I have always been aware of the Moors; but probably mostly from history lessons at school – and then probably church history where everything was given a very Christian slant. In reality, not only were the Islamic/Muslim/Moorish dynasties centres of learning with great teachers and philosophers from all the main religious groups (Muslim, Jewish and Christian) but they have also left a marvellous cultural and architectural legacy. This write-up of my trip to al Andalus suffers somewhat from being undertaken almost two years after the experience. I have lost a lot of memories, reactions and information. I’ve had to dig around on the Internet to identify a lot of photos in the slide show and fill in gaps of information. Madrid

Frustratingly, I was timed out or thrown out by my email server and lost a couple of hours work. I never sought to recreate it. I don’t even have photos to jog my memory, as with physical structures such as castles, cathedrals and mosques. I can say, however, that, while Madrid was a very different experience to the culture, history and architecture of other places visited, it had its own intense attraction and satisfaction. In addition to time spent in the Prado and the Archaeological Museum; and walking around the key landmarks, I more or less stumbled across another attraction: a Ballet Flamenco performance in the Teatro Espaňol, in the neighbourhood of my hotel. It was a new program called Lluvia by Eva Yerbabuena. In fact, as I discovered later, it was a one-night premiere performance. Eva Yerbabuena is a highly acclaimed and award-winning flamenco dancer who set up the company Ballet Flamenco. It was a great evening and a fantastic take on flamenco: layers above the tourist-oriented performances. Eva Yerbabuena subsequently took Lluvia to London and Athens. It was all pretty special. You can see a bit of the show here.

Toledo is a World Heritage site. The old town goes back to Roman times and also displays much of its Moorish history – as with Seville and especially Cordoba. Under Moorish rule, Toledo was a substantial cosmopolitan city of considerable cultural, academic and political influence. Its fall to the Christian king Alfonso VI of Castile in 1085 was the first time a major city of al-Andalus had fallen to the Christian forces. Fortunately for Toledo, its libraries and store of manuscripts were preserved; and many translated into Spanish and Latin, thus extending a huge store of knowledge into the Christian world. Toledo was a one-day train trip from Madrid. Once I discovered it was so close to Madrid, it became a must-visit place. Its attraction or fascination goes way back to high school days. The Alcazar of Toledo

The alcazar today is unmissable and unforgettable. It sits at the pinnacle of the city and is dominatingly visible from everywhere. It wasn’t hard to imagine the near impossibility of conducting a successful siege; and the isolation and desperation of its defenders. The disappointment for me was that the alcazar was closed on the day I was there – and seemingly had been for some time. It was being extensively renovated. So I didn’t get to see inside. Churches and Monasteries

Somehow I found the Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes on the edge of Toledo. I can’t remember how this came about. Anyway, it’s an historic monastery founded by King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile to commemorate their victory at the Battle of Toro (1476) over the army of Afonso V of Portugal (according to Wikipedia).

City Walls and Gates The city still has substantial remnants of its old walls, mostly dating back to Moorish rule. A walk around the ramparts of Toledo showed the cunning Moorish design of zig-zag approaches to ensure any enemy intrusion was subject to maximum vulnerability. There are still several massive gates in the old walls. Toledo was a so worthwhile visit. Seville Seville might justifiably call itself the city of opera. Not necessarily in the sense of opera performances but of opera settings. Bizet’s Carmen is set in Seville, notably in the precincts of Seville’s famous bullring. Rossini’s The Barber of Seville provides a less tragic perspective of life in Seville. Seville provided the setting for two of Mozart’s greatest operas: The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. Verdi also used Seville for one of his operas – but one I’d never heard of. I didn’t go to any barbers in Seville, didn’t get into any of Figaro’s predicaments, and certainly didn’t emulate any of Don Giovanni’s (or Don Juan’s) licentiousness – evidenced by not suffering his just fate; but I did visit Seville’s bullring. La Giralda

La Giralda started life as the minaret of what must have been a grand mosque. It dates back to the late 12th century during the Almohad period in Seville. The tower was – and still is – regarded as the culmination of Almohad architecture. It is considered the finest of the three great Almohad minarets still standing (the other two are in the Moroccan cities of Rabat and Marrakech). In fact, the tower of the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech served as a model for La Giralda. It is said that La Giralda was so venerated by the Moors that they wanted to destroy it before the Christian conquest of the city in 1248. This was prevented by King Alfonso X, who declared that "if they removed a single stone, they would all be put to the sword." La Giralda was thus preserved. Shortly after the reconquest of Seville by the Christians, the original mosque was consecrated as a cathedral. When an earthquake badly damaged it in the mid-14th century, it was decided to replace it with a new cathedral. The tower survived the earthquake, but the copper spheres on the tower fell and were replaced with a cross and bell. The new cathedral incorporated the tower as a bell tower. Later, during the Renaissance, additional levels were added to the tower to accommodate a belfry. Balconies were also added.

The most famous sights in the cathedral are the gilded altarpiece (Retablo Mayor) and the tomb of Christopher Columbus. The Retablo Mayor is supposedly the largest altarpiece in the world. It consists of 36 gilded relief panels depicting scenes from the Old Testament and the lives of saints. It took over 80 years to complete (1482-1564). Large iron grilles, forged between 1518 and 1532, separate visitors from the altarpiece. The cathedral museum is housed in the main sacristy, where there are several valuable paintings as well as the large silver ostensorium (monstrance). Near the main entrance to the cathedral stands the large funeral monument to Christopher Columbus, which supposedly contains his body, which was brought there from Havana at the end of the 1890s. The sarcophagus is carried by four large statues, representing the kingdoms of Aragón, Castile, León and Navarra. The Patio de los Naranjos (Orange Tree Courtyard) was originally the courtyard of the former mosque; and, along with La Giralda, survived the 14th century earthquake. The patio is now part of the cathedral. (Orange tree courtyards seem to be a feature of the Moorish mosques.) A large portal, the Puerta del Perdón (door of pardon), built in the 12th century by the Moors, leads to the patio. At the centre of the patio is a stone fountain which dates back to the Visigoth or possibly even the Roman era. Real Alcazar of Seville (Royal Palace) The Real Alcazar is the Royal Palace of Seville. The heart of the complex is the Palace of King Pedro I, who constructed his royal residence on the site of a Moorish palace.

The palace is arranged around a number of patios. Over the years, other monarchs kept expanding the palace, resulting in a diverse complex with different architectural styles. It was interesting to catch recently an episode of Ancient Megastructures on the NatGeo channel. It was about Alhambra in Grenada, most of which was constructed late in the life of al Andalus, as the Christian Kings were reducing al Andalus to the Emirate of Granada. It seems that some sort of mutual coexistence arrangement had developed between Pedro I in Seville and Muhammed V, Sultan of Granada, to the point where Muhammed was benefiting in his contribution to the construction of Alhambra from the designs and decorations of Pedro’s palace. The result was that the later stages of Alhambra incorporated much that was designated Mudéjar style and even Christian style. Regrettably, I had not been aware of Alhambra when planning my trip. I became aware of it in Cordoba. I would have loved to have seen it but that will have to wait. Murallas

The Romans were the first to build city walls around Seville as early as in the first century B.C. At the end of the Roman Empire the wall was largely destroyed by the Vandals, only to be rebuilt later by the Visigoths. The walls that can be seen today date back to Muslim al Andalus. Construction of the wall started in the 11th century and was completed in the early 13th century. The 6 km long wall with 166 towers and nine gates encircled the whole city. At the time Seville was considered Spain's best fortified city. There are still several towers standing. The tallest tower on the murallas is known as Torre Blanca (White Tower). Several towers that were originally part of the defensive wall around Seville have survived in other parts of the city, including the Silver Tower and the Golden Tower (Torre del Oro), Seville's most famous tower. Plaza de Toros de Maestranza This is Seville’s bullring.

My first concern was whether it was bull fighting season and, if so, whether I would try and attend a bull fight, despite my instinctive abhorrence of the activity. As it turned out, it wasn’t the season and I didn’t have to grapple with my conscience, although I couldn’t help feel an unconscionable fascination to experience the spectacle. You can visit the bullring only by a guided tour. That was fine. They took place every half hour. The tour pointed to the various entrances to the arena, each designated for a specific function, such as the entry of the torero, the entrance of the bull and the entrance of the picadors on their horses. There’s a chapel, dedicated to the Virgen de la Caridad, where the toreros (bull fighters or torreadors) pray before entering the ring; and an infirmary - in 20 per cent of bullfights the torero needs emergency treatment. The bulls aren't as lucky. Alameda de Hercules Not least of all that deserves mention is the Alameda de Hércules – a large plaza, built as a public garden in 1574 and extensively renovated in 2008. It purports to be the oldest public garden in Europe. It’s probably not a tourist attraction as such. It’s just that my hotel was around the corner so it was an unexpected discovery. From the time it was built in 1574, four columns were placed to mark off the promenade. They had been found in the remains of a Roman temple dedicated to Hercules which once stood in that part of the city. On two of the columns, statues were placed, one of Julius Caesar and one of Hercules. In the second half of the 18th century two more statues, lions with shields representing Seville and Spain were placed on the remaining columns at the other end of the promenade. It’s well known for its surrounding bars, cafes and restaurants. Or so I read. Cordoba Cordoba was perhaps the greatest centre of Al-Andalus. For a century and a half, the Cordoba Caliphate ruled Al-Andalus. Under the Caliphate, Cordoba became the largest city in the then known world, overtaking Constantinople (Istanbul). Within the Islamic world, Cordoba was a leading academic and cultural centre. The Mezquita

It hasn´t been a mosque as such for eight hundred years, but still has the look of one. It has to be one of the most amazing buildings in the world. It´s right up there (at least in the impact it had on me) with Aya Sophia in Istanbul and the Taj Mahal in Agra. It started life in the 8th century when a mosque was first built over a Visigoth Christian church of the 7th century. The first mosque was extended four times over a few hundred years to eventually accommodate 40,000 worshippers in its final form in the last years of the 10th century. The size and antiquity are mind-boggling. Each extension copied the essential interior design of the first section, but there are some differences in flooring and floor levels. It has the most spectacular Mihrab (the Mihrab is probably equivalent to the tabernacle in a Catholic church, in the sense that it´s the most sacred part).

The Mezquita has an orange tree patio with fountains and, of course, a minaret (or did; it´s now a bell tower remodelled under Christian rule). All in all, it is simply a stunning intertwining of Mosque and Cathedral, with all the trappings of Muslim and Christian architecture and religious atmosphere. I wrote about it and the significance of its transept – El Crucero (the Crossing) – on the Fireside page under the heading El Crucero. You can read more about the Mezquita there. Cordoba’s Alcazar

The alcazar was built in 1328. Ferdinand and Isabella later governed Castile from the alcazar for eight years in the 15th century as they prepared to reconquer Granada, the last Moorish stronghold in Spain. It was here that Christopher Columbus presented to Queen Isabella his plans for an historic journey to the Americas. For nearly 300 years the alcazar was the headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition. Interestingly, I recall that I came across several ‘museums’ of torture instruments in Toledo and Cordoba. I guess it’s a Spanish thing. The alcazar houses Roman mosaics from the 2nd and 3rd centuries, as well as Moorish baths. The alcazar is surrounded by impressive gardens, which, although established in Christian times, are typically Moorish in design. Roman Bridge

At one end of the bridge there is the Calahorra Tower, which defended the south side of the Roman bridge. It shares 12th century Almohad and 14th century Christian components. The tower is now the site of the Museum of the Three Cultures – there’s more on this aspect on the El Crucero page. At the other end of the bridge is the Puerta del Puente (entranceway of the bridge) – one of the gates of the old walls of Cordoba.

Extensive portions of Roman walls, maintained and extended by Moorish and Christian rulers, still stand today. The walls stayed the same from the Muslim conquest in 711 until the fall of the Caliphate in 1031. Subsequent Moorish and later Christian rulers fortified and expanded the walls for their own defensive purposes. In the 19th century, stretches of wall, towers and gates were torn down to make way for new streets. Today, the most significant remnants of the city's ancient towers and gates are la Puerta de Almodovar (Almodovar Gate) and la Puerta del Puente (Bridge Gate).

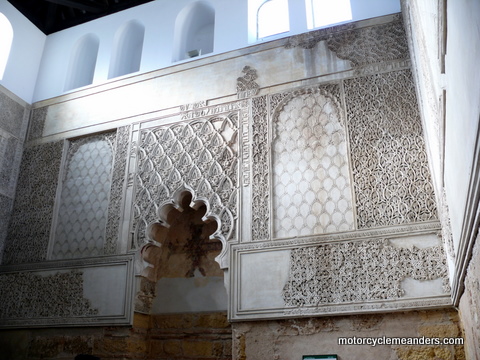

At the centre of the quarter is the synagogue, one of only three originals remaining in Spain. The interior includes a gallery for women; and plaster work with inscriptions from Hebrew psalms. Its main, beautifully restored wall has a semi-circular arch where a chest with the Holy Scrolls of Law used to be kept. Crossing the Straits I Having somewhat dejectedly made my way to the port, I was directed to the window of the company that had the next ferry – at 5.00pm. However, remembering that I read on the Internet that the timetables are not always adhered to, I instead went to the window of the company that had the 2.30pm ferry. It was about 4.00pm by now. Sure enough, they were still selling tickets for the 2.30pm ferry. As it turned out, it was a slow trip owing to the swell and then being held off shore for a long time before being allowed to berth. I finally got to my hotel in Tangier. It was old but okay. The room had a stone floor with lots of peeling paint in the bathroom. But it was clean and spacious for all that – even quaint, so suited the atmosphere of Tangier. Thus began my Morocco tour. Photo Album |