|

|

Dalmatia May-June 2010 Dalmatia is a region of Croatia. The title, however, is a shorthand way of referring to a tour of four Balkan States: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro – all previously component parts of the former Yugoslavia; as well as a few days in the Dolomites of North Italy. The tour started in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. The tour was organised by and undertaken in partnership with the Slovenian operator, Adriatic MotoTours. This page is an edited version of the daily blogs I did during the trip. Some pre-trip blogs have been saved in a PDF document: Early Blog Postings. I also prepared a rough guide to the tour – all simply copied and pasted from Internet sites. It hopefully offers an easy guide to places on the tour, which, of course, are spread through several countries: Dalmatia – A Rough Guide to the Tour

Slovenia had never been a comfortable fit in the old Yugoslavia, although you might say that about most of its former component parts. Its culture and history had been closer to Austria, so it would feel that it had regained its heritage by being part of the European Union rather than the old Soviet bloc. Our first full day in Slovenia was sight-seeing in Ljubljana. This is not so big a country or city. Slovenia’s population is only around 2 million; and Ljubljana’s less than 300,000. However, Ljubljana seems larger than its population would suggest, possibly because you don’t get the enormous land-occupying spread we tend to get in Australia. The city has a buzz of activity, traffic and people that belies its size in population terms. The old town is the centre of its history and life; and its big attraction. There’s a river running through the middle of the old town making its many bridges a key feature. Folklore has it that Jason of Argonaut fame sailed down the river to Ljubljana with his golden fleece.

It’s a very relaxing city in the old quarter. Nothing like the bustle of the new section of the city. We ambled about, visited the key attractions, scaled the castle hill (in the funicular), and enjoyed lunch and some local wine along a cobbled street. The next day, we headed out to meet our local operator and collect the bikes. Mine was BMW’s R1200GS. There’s always some apprehension attached to riding a bike that’s new to you on roads that are new to you and, not least, having to ride on the right-hand side. With a car, the driver’s seat on the left is a constant reminder of the need to stay right, but with a bike you have no such aide. Thanks to one of my Wednesday ride group, I had had an opportunity to ride the BMW R1200GS before. Bill had invited me to take his 1200GS down the Clyde escarpment one day. At least, that now took the fear factor out and left only the general apprehension of new roads and the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

Map of Route This map indicates the route taken, but with some inevitable straight lines. Not all roads are indicated accurately; and there will likely be changes for each tour.

Plitvička National Park, Croatia It was satisfying to get the bike and get the feel of it during a gentle run through the light green forests and rolling hills as we passed from Slovenia through border control to Croatia. As in most of the Northern Hemisphere, the forests are a blended mix of light greens, all the starker with the fresh growth of Spring. It’s striking when you’re more accustomed to the much deeper and blue-tinted greens of the Australian bush. Our destination was the Plitvička National Park (plit-vich-ka), a UNESCO-listed World Natural Heritage Site. Its central attraction is a network of interlocking lakes cascading through forests and ravines until they join at the top end of a large lake, only to flow out in another set of falls and cascades. The water is sparkling clear. The paths of the cascades change with conditions as the underlying porous carbonate rock (tufa or travertine) takes on varying shapes and formations. It’s all quite stunning. So stunning, in fact, that I have created a photo album dedicated to the park. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

It was a long day. Only 400km, but with time taken to refuel the group (twice) and have coffee, lunch, photo stops and a bit of sight-seeing, we didn’t get to Sarajevo until after 6.00pm. But what a day it was: great riding through constantly changing topography but with sobering reminders of the horrors and atrocities of the Bosnian war from 1992 to 1996. By then, I felt thoroughly comfortable with the big 1200GS. It got a decent work-out with lots of winding roads through lush green forests, around the steep edges of hills as we followed their sides in and out to the tops and down again, sweeping over expansive green fields (without much sign of agriculture) and across sections of rocky semi-barren plateaus obviously above snow-lines in winter judging from the signs indicating the need for chains. Littered along the way were many destroyed and abandoned villages, vestiges of the senseless destruction and cruelty exposed during the Bosnian War – with guilt spread across more than one protagonist. You could hardly imagine the long-lasting impact made on communities and families as one side sought to project its prejudices and ambitions over the other. Some villages had started to rebuild as new houses, perhaps a few repaired, were dotted amongst the rubble of the crumbling ones. Others were totally deserted. I was struck by the absence of people, even in the occupied villages. There were no comings or goings, no people sitting around having coffee and chatting; just a few isolated folks attending to a garden or burning some rubbish. It seemed eerie. It was with some relief that he arrived at a sizable town, Livno, to find a town square, with newly planned features, albeit surrounded by dilapidated buildings – but, at least, with lots of people dining and drinking. We had lunch their enjoying watching the young people passing by, talking, laughing, and flirting with one another – pretty much behaving as young people anywhere.

Sarajevo is sometimes described as the Jerusalem of Europe, meaning it’s a place where the three great religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam have long lived side by side. The city has more than ninety mosques dating from the Ottoman Turkish control of the city for over 500 years. It had several Synagogues prior to World War II and a few still exist today. There are basilicas of both Catholic and Orthodox Christianity. It’s the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina and has a population of about 500,000.

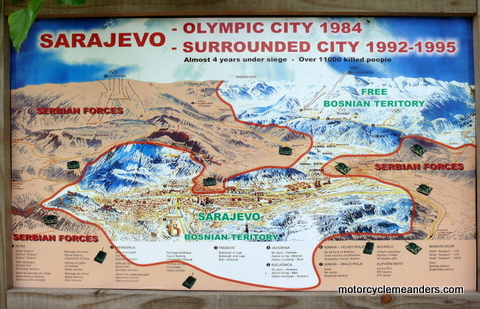

Sarajevo sits at the centre of a unique ethnic, religious and political complexity that is Bosnia and Herzegovina; and that still defies permanent resolution. Invasions, wars and uneasy tolerance have been part of life in this part of the world for over a thousand years as early Slavic settlers evolved into different political and religious entities. The undercurrents of prejudice, intolerance and ambitions of political dominance were no more starkly and tragically evident than in the Bosnian war of 1992-1995.

Sarajevo was also the site of the event that triggered the First World War, namely the assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand and his wife. He was the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. I recall learning at school that this was the cause of World War I, but that was a simplistic view no doubt tailored for a 14-year-old. However, it’s still considered the catalyst that brought the war on. There’s a plaque by the Latin Bridge where it all happened. You might recall that Sarajevo was the site of the Winter Olympics in 1984 – a first for a Socialist State (Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of the Yugoslav federation in those days). All in all, Sarajevo is a unique city: one of glory and devastation; one of three ethnic and religious groups; but predominantly a Muslim enclave in a Christian surround. Mostar (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

We wound and twisted along the river canyons, through tunnels into neighbouring valleys, up and over several ranges and across lush green countryside before encountering increased challenges when one of the back roads narrowed as its deteriorating condition ate away at its edges and left the rest mightily pot-holed. But that was a relatively short stretch. The rest was motorcycle Nirvana. Mostar was our destination. It was the most heavily bombarded city during the Bosnian War as, this time, the Croatian forces – seemingly equally brutal as the Serbians – tried to destroy everything Bosnian, including the Muslim Bosniaks. The old town of Mostar is more spectacular and charming than some travel information suggested, dismissing Mostar as only worth looking at the bridge. They had sold the town very short. However, there’s no doubt the bridge is the centrepiece. And what a story that is!

Mostar has obviously not done so well with re-building, except for the old town. Many bombed–out buildings still provide vivid pictures of the war days. Here is a photo album of Mostar that seeks to capture the constant reminders of its war-torn past. It was heartening, in the midst of so much destruction and ethnic animosity, to return to the hotel after a pleasant dinner in the old town to find a high school formal in full swing in the hotel’s ballroom (cum dining room, bar and extended foyer). The school, Turistic School (TUSC), I was told, has about a 70/30 mix of Croatian and Bosniak students. The formal resounded with all the thump and fun of any high school formal anywhere. Here, hopefully, was a generation that would break through the ignorance and prejudice of their parents and forebears; and provide a more enlightened future for their country.

Getting to Zabljak involved a long climb on the narrowest of roads so far (and, we’re assured, the narrowest of the trip!), with a generous dollop of tight switchbacks. There were sufficient on-coming cars, vans and trucks to make sure you kept to your line on the corners and timed the switchbacks to avoid the trucks, which simply can’t do them staying on one side of the road. Eventually we emerged onto an expansive lush green plateau surrounded by rocky peaks with the last of the winter snow draped over them. The plateau, mostly treeless, ran for miles, with scattered small settlements and summer-grazing sheep. On the far side from our approach the forests resumed and we seemed to start the run down when the sizable ski resort town of Zabljak appeared. A feature of a lot of the mountain roads all around here are the tunnels. They vary enormously in length, some with turns in the middle and none with internal lighting. Your headlight doesn’t seem to do much, especially when you’re wearing sunglasses. A few longer ones involved a quick flick of the visor and a drag of sunglasses down your nose to open a narrow crack of unhindered vision into the dark. Then there’re the speed traps. One tunnel that quickly became part of our trip’s folklore had a 40 kph limit as you approached it – with a police radar trap at the exit. Four of us had been riding together at that stage (small groups often form spontaneously and just as quickly dissolve as riders stop for photos or decide to slow down). The hapless lead rider duly sacrificed himself as wood duck on emerging from the tunnel at a little over the posted limit. As number 3, I took the only practicable course and rode on, as did number 4 – eventually followed by number 2, who obviously had had a fleeting moment of camaraderie which he quickly suppressed. Laurie’s plight wouldn’t have been so bad had it not been for the faster speeds of following bikes, all duly recorded on the radar and each successive increase further deepening the ire of the police officers, who wanted to hold Laurie responsible for each and every breach. He was very reluctantly freed to continue his journey.

Petrovac, Montenegro

The initial run down from Zabljak was on a much better road than the way up, but no less winding and with its share of switchbacks. We then reached a fast running river that the road clung to for several miles through deep, rugged gorges. Apart from the spectacular scenery, a road that hugs a river along its course through the mountain passes and gorges has the added benefit, usually, of winding in a consistently predictable manner, making for brisker and enjoyable riding. Without warning, the road would change course, leave the river and head up the mountain side though more twists, turns and switchbacks.

Eventually the dead-flat (at least on the day we arrived) Adriatic Sea comes into view by way of a small bay with high coastal walls around it. The road winds its way down the rest of the mountain and delivers you at the delightful sea-side town of Petrovac. Our hotel fronted a 600m beach that arcs around the light blue waters, with the town buildings and promenade following it. The water, even so early in the summer season, was a very pleasant temperature. Having arrived early afternoon, there was time for the interested and willing to swim, sit around on the beach or retreat to a charming bar on the water’s edge at one end of the beach. A few of us swam to the bar and arrived by skirting the initial rocky protrusions and entering via a break in the rocks. Dubrovnik, Croatia

High in the Lovćen National Park, the mausoleum of Petar II Petrovic-Njegos, Montenegro’s most revered poet, is perched on the top of a mountain peak at 1660 metres (not much short of the height of Mt Kosciuszko at 2228 metres). Reaching the mausoleum necessitated a climb of over 400 steps from the parking area at about 1500 metres! Arriving at the mausoleum at 11°C, it was hard to imagine we had been swimming in Petrovac the day before surrounded by a warm 28°. We descended the 1500 metres to sea level on the Adriatic in about 40 minutes to a welcoming temperature of 25°. A different road down was, contrary to expectations, even narrower than encountered before – so narrow that passing on-coming vehicles necessitated stopping to negotiate avoidance of side mirror contact. Slow and careful around every increasingly tighter turn was the governing process. Even when the road widened on leaving the park, it had no choice but to inch its way down the steep mountain side in a series of switchbacks that defied passing anything on them. Not that they were any deterrence to the tourist coaches. Passing them even on the gentler curves required a double shuffle as the coach first locked you in a small triangle of space and then moved forward to let you escape.

From there it was a pleasant run along the coast back into Croatia – another border crossing – and onto the fortress town of Dubrovnik for a two-night stay. Dubrovnik was built on maritime trade in the Middle Ages and was said to be the only city state in the Adriatic to rival Venice. Its fortress walls and strategic location provided an effective defence against would-be invaders, such as the Ottoman Empire, for many centuries. Now it’s an attractive and popular tourist destination. It’s not often you find one of these old walled cities that has the complete wall intact. Dubrovnik’s city walls stand proudly surrounding the entire old town as they have done for centuries, although one presumes with considerable restoration along the way. In fact, Dubrovnik wore some damage during the Balkan wars of the 1990s but mostly this has been repaired.

Lunch in the sunshine of the harbour side, with a sampling of some fine local white wine, was a perfect culmination of our introduction to Dubrovnik. I later found a couple of history museums that were interesting enough. Then the main attraction: a 2km walk around the top of the walls, up several sets of stairs as the wall changed height to fit the terrain, climbing to the top of corner towers, walking along the edge of tall walls that dropped perpendicular into the sea. All with spectacular views of sea and city. The old town is jam-packed with narrow laneways, churches, monuments and other distinctive architecture. It wasn’t hard to spend a day taking in such a unique place. The walk back to the hotel was about 3km through the new town, which has spread up the mountain side from the old town and along the peninsula and over the point. The new town also has its attractions and provided a convenient and enjoyable place for an al fresco dinner. Korčula, Croatia

However, just before we got to Ston, I was too slow in reacting to the flashing headlight of an on-coming car and got pinged by radar at 102 kph coming into a 70 kph zone (no town in sight – just a bend coming into a long downhill stretch). They have the practice, curious to us, of posting speed limits where we would normally have only advisory speed signs. The young Croatian police office was very polite. He wanted to see my driver’s licence. He asked if this was my first time in Croatia. He took me to his car parked discretely well off the road. He showed me his booklet with speeds over the posted limit and fines. At 32 kph over the limit, the fine was 2000 kuna (about 270 euros or $400AUS). He said it was the law that I pay immediately. I asked could he simply give me a warning. He solemnly shook his head in a troubled, pensive manner and said softly, “No, no, not for that amount over the limit.”

For quite a while an uncomfortable silence prevailed. Then his ‘bad cop’ routine of dismissing the possibility of a warning transformed into a ‘good cop’ routine as he eased the agonising silence to an end by looking at me and, as though thinking aloud, offered an alternative way out. “Well, Mr Robert, my boss checks all the recorded speeds so I have to fine you. However, since this is your first visit to Croatia, I can do something for you. I can punish you by fining you only half the amount, at 100 euros, and erase the speed from the radar; but if I do that I can’t give you a receipt.” I had initially thought, as he started the ‘good cop’ routine, that he was going to let me off after all, but that obviously wasn’t going to happen. It was now my turn to let the pregnant pause gestate a while longer as we both stayed silently pondering. I finally broached a gentle question. “How about you punish me with a 50 euro fine and wipe the speed off the radar?” He was a bit too quick in responding, “But you realise I can’t give you a receipt?” “Yes. I understand that.” I then fumbled with various notes, being very careful to ensure the couple of 100 euro notes I had remained tightly concealed in my wallet. I pulled out a 20 and a 10 euro note and some other note, which he quickly dismissed as a Bosnian Mark. I prevaricated with a bit more fumbling before putting the 20 and 10 euro notes forward. “How about 30 euros?”

“Goodbye, Mr Robert.” And that was the end of that. Never belittle the benefits of bartering in Bali! From the tip of the Pelješas Peninsula, we crossed by ferry to the island and town of Korčula in time for lunch. Korčula is reputedly the birthplace of Marco Polo who features so prominently around town that you might assume the family moved house quite a few times. The idea had been to spend the afternoon exploring the island at will on the bikes, but a rainy arrival and some wine at lunch dictated settling for walking around the town and exploring its marina, streets and towers. In the evening we returned to the old town and dined in one of its cosy restaurants. The next day, we were on our way in time to catch the 9.00am ferry from Korčula to the mainland for a ride back along the Pelješas Peninsula; then up along the coastal roads heading north again. Hvar, Croatia

The sheep mentality got the better of most of us once back into Croatia. Someone – who must remain unnamed for his protection – took a wrong turn and had most of us follow him. Confusion took control for 30 minutes or so before we satisfied ourselves as to quo vadis? We dribbled into the small ferry town of Drvenik sufficiently spread out to ensure missing a ferry to the Island of Hvar; and having to wait a couple of hours for the next one. A picnic lunch on the pebbly beach under the shade of Cyprus trees easily filled in the time. It was only a half-hour hop across to Hvar, followed by an 80 km winding and twisting ride along the entire length of the island to Hvar town at its northern tip. There are several small villages on the island, lots of wineries and an abundance of lavender.

The old town of Hvar – dating back to the 15th century – whose wide promenade encircles the small harbour decked with luxury boats and charter craft, has a huge town square dominated by the cathedral of St Stjepan. Overlooking the town, spread across a hill at the back of the town centre, is a massive fortress dating back to the 13th century. It provided protection for the town folk against invading Ottoman Turks who ransacked and burnt the town during their empire building days in the 1500s. A particular treat for dinner in Hvar was a boat trip from our hotel along the shore from the town, past the harbour and around a few points to a tiny village tucked away – almost hidden – in a small cove. It was a dinner excursion, so, as we approached by boat, we obviously wondered which of the three or four water side restaurants we were destined to dine in. None! A kilometre or so walk along a rough track led us to a very rustic-looking stone building in a large olive grove, in which our tables were set. We were treated to a feast of home-made everything: olive-based grappa (lozje in Croatian) as a welcoming aperitif, octopus (large!) in a fabulous red wine sauce, cigar-sized prawns, whole grilled fish, calamari...and anchovy bread: much of this prepared in a massive stone oven driven solely by the carefully tended wood fire. It was quite a memorable two-night stop in Hvar. Novalja, Pag Island, Croatia

A few of us headed out early and found our way by a narrow back road to Stari Grad, the oldest settlement on the island (Stari Grad means old town). As we wound around the green hills to Stari Grad, we were fascinated by the intersecting network of stone fences all over the sides of the hills. Turns out they came about as part of the process of simply clearing the stones to make way for planting lavender. Stari Grad was a quaint old town, with its town square at the peak of a protected waterway coming in from the Adriatic. It was certainly worth an hour’s walk and coffee at the centre of town.

The island of Pag, along with many other islands along this more northerly part of the Croatian coast adjacent to the Velebit Mountains, has a windward side that is starkly barren from the force of the Bora; and a leeward side that has a lush salt-laden green cover from the Bora’s picking up sea water and depositing it over the peaks. The hotel was a very welcome sight in the final minutes of the setting sun which seemed to delay its departure until we got in. Sežana, Slovenia

It was another good mix of coastal and inland riding. First, we trekked along the Dalmatian coast of Croatia; then headed into the hills and rolling farm lands of the hinterland. While the switchbacks were fewer than in the mountains, there was no end to the ups and downs and arounds. The coastal riding has its own set of attractions as the road usually winds around the steep hill sides, providing stunning views of the maze of islands spread across the Adriatic.

This was Sunday. We were introduced to Sunday riding Slovenian style. Winding our way through some great twisties in the Goteniška Mountains in the south of Slovenia, soon after crossing the border, we encountered hundreds of boy (and probably some girl) racers who milled around in large groups enjoying the spectacle of their fellow riders competing in spontaneous time trials around the turns. It was just a little startling at times to have a screeching sports bike go flying past you in a tight turn. As we passed through the last of Croatia towards Slovenia, we probably should have guessed at something like this from spotting a number of tight-fitting leather-clad riders, some with velcoed on, even tighter-clad pillions (one with matching stiletto ‘riding boots!’) – and some with treadless racing tyres on their sports bikes! We managed to get to the Caves with less than a minute to spare before they closed off the final guided tour of the day. The Škocjan Caves have some large limestone caverns, but their main attraction is their enormous underground canyon. The fast-flowing Reka River charges through a nearby gorge and disappears underground into the cavernous underground chambers of the cave system, tumbling down underground waterfalls and racing through narrow chasms. There is a walking track hewn into the side of >40-metre-high canyon walls. Everything is wet as a fine mist fills the canyon. A great spectacle! A short ride after emerging from the caves around 7.00pm had us in Sežana for the night. Corvara, Italy

Corner marking came into its own as we made our way through more complicated routes and busier towns in Italy to weave our way closer to the Dolomites – a large section of the Italian Alps and one of Northern Italy’s popular ski areas; not to mention popular cycling and motorcycling areas. The first part of our Italian experience was across fairly flat country before seeing the distant Dolomites rising ahead of us. Then it was a long climb into the mountains and up over a couple of passes to the town of Corvara, tucked away in a valley high up in the Dolomites. It was a two night stay here, so we had the opportunity to do some exploring around the area.

Some of us had a lazy day; some went into town for some shopping; some ventured out for rides across closer mountain passes. Five of us headed out about 9.00am to tackle some of the neighbouring passes. We did a circuit of about 60km that crossed the tops of five passes, each one requiring a long, winding ascent to and descent from the top of the pass, with lots of end-to-end switchbacks. I couldn’t boast having done them all as smoothly as I would have liked, especially when meeting oncoming vehicles on the right-handers (think left-handers in an Australian context); you don’t have any margin at all to expand an already tight turning circle. But just a great riding experience. Even so early in the summer and on a mid-week day, there were motorbikes everywhere: in towns, going up to the passes, coming down, and having coffee at the tops of the passes. I was told that in the height of the summer and especially at weekends, there is virtually one continuous line of motorbikes in each direction on every road. Little wonder so many places have “Motorcyclist Welcome” signs displayed! Bovec, Slovenia

Back “Home” in Ljubljana, Slovenia Once out of the Julian Alps, it was mostly a motorway run back to Ljubljana, with a lunch stop at the attractive lake that provides a centrepiece of the picturesque town of Bled. Soon, we were back at our starting point: Ljubljana, capital of Slovenia. As with past meanders abroad, you invariably feel despondent when you realise there’s only two or three days to go. But by the time you arrive, the despondency transforms itself into a sense of triumph and relief: triumph because of the accomplishment and satisfaction of a great trip; and relief because you’re back with no damage to you or your bike. In fact, while you want to extend the trip when you’re a few days out, by the time you’re back you feel that enough is enough. Cobble-stoned switchbacks must rate with curves, including switchbacks in pitch dark tunnels, as amongst the more interesting motorcycle experiences of the trip. So, it’s now over. A great trip, with some of the best riding roads and challenges you could find anywhere. Photo Album Here is the photo album of the tour.

|