|

|

Jordan April 2008

The Jordan component started as a three-day trip focussed on Petra. But as my research expanded, the trip grew to a week’s stay. It could easily have been longer; there was so much of interest. But I limited myself to the week and, therefore had to forego some key sights. The tour was undertaken in a car and accompanied by Khalil, my local driver, guide and fixer. We travelled from Amman along the King’s Highway to Karak Castle; then across to the main highway to continue south, cutting back into the King’s Highway to visit Shawbak Castle and the City of Petra. We returned to Amman on the main highway, but continued through to Jerash before coming back to Amman. Map of Jordan Tour Here is a map of Jordan indicating the route I followed. You can interact with the map by using the arrows and the + and – signs. You can also change to ‘sat’ or ‘Earth’ view and zoom in to better appreciate the terrain. If you're a potential visitor, make sure you follow the King's Highway south from Amman rather than the main desert highway, at least, as far as Kerak.

Amman

My first impression of Amman was a city in monochrome. Every building seemed to have the same light beige hue. They were packed so tightly that the whole city could have been a giant Legoland. Closer-up, of course, as you wandered the streets of old Amman, you came to appreciate the diversity hidden behind the monochrome facade. Amman was an interesting mix of antiquity, long-established traditions and modern living.

The centre of modern Amman is a bustling city of shops of all sorts, cafés, street sellers and people going about their daily routines. I found several sights intriguing and worth capturing on camera.

Philadelphia From the Citadel, you can pretty much see all of Amman, but you look directly down to the centre of the old Roman town of Philadelphia, marked by the huge Roman theatre and the sprawling Roman forum or open market place. I walked down the hill from the Citadel and investigated the forum and theatre, the latter with its surprise embellishments of back-stage venues, now galleries and museums. Mt Nebo The venture out of Amman began with Mt Nebo about 40kms southwest of Amman and high up over the Dead Sea and Jordan Valley. From a viewing area at Mt Nebo, you have spectacular views of the northern end of the Dead Sea and across the Jordan River to Jericho, some say the oldest city in the world; and the West Bank territory, of such contemporary political sensitivity. Had the day been less hazy, you would have seen all the way to Jerusalem.

Looking out over the Jordan Valley would have been impressive in any context, but it was all the more so – and moving – to ponder the scene knowing the deep-rooted Jewish, Christian and Islamic reverence for Moses and the significance of his history to these three great monotheist religions. You were looking across to the Holy Land, which, by whatever name, is sacred today to all three religions. Mt Nebo was as far as Moses got leading the Israelites to the Promised Land. The Brazen Serpent Monument, inspired in part by the bronze serpent Moses created in the desert, is probably about the spot from where Moses viewed the Promised Land. He was forbidden to venture into it, however, as punishment for his doubts along the 40-year route from Egypt. He died somewhere in the vicinity. I was particularly struck by the rugged, desolate, uninviting nature of the countryside: rock, steep slopes, dry and brown, except for some greenery in the distance around Jericho and along the river. There were no lush, rolling hills or fertile valleys. Yet this was the Promised Land, the land of milk and honey, the land the Israelites had been dreaming of and aspiring to for 40 years. I couldn’t help thinking that you’d have had to be wandering aimlessly and desperately in the desert of 40 years to think this was anything close to what you might have been led to believe was the Promised Land! Madaba

The town has an interesting story. More than 3,000 years ago, Madaba was a border town of the biblical kingdom of the Moabites. A Christian community existed there around 450 AD. The Persian invasion in the 7th century AD and an earthquake in the 8th century AD resulted in the town being virtually abandoned until the late 19th century. In 1880, Muslim tribes expelled Christians from Al Karak, much further south, who then made their way to Madaba, but were allowed by the Ottomans to occupy only sites of former Christian churches. It was this series of events that uncovered the treasure of Madaba’s mosaics. Early Christian monks, on settling in the region from the 5th century or earlier discovered clay and stone that they recognised from their experience and expertise to be well suited for mosaics. They obviously set about creating them with great gusto, given the virtual treasure trove that eventually emerged after only a few hundred years of early Christian occupation. The mosaic map of the Middle East in the church of St George was discovered in 1896 and has been dated at about the middle of the 6th century AD (gleaned from the presence and absence on the map of certain buildings in Jerusalem whose dates of erection are documented elsewhere). The original map would have been about 25m x 5 m and would have contained more than 2 million mosaic stones. Madaba today is a changing city. It has lots of recently constructed elaborate homes – a result of the influx of over 1m people from Iraq following the war in that country, who have bought land from the Bedouin owners. King’s Highway

The King’s Highway started at Heliopolis in Egypt, came across the Sinai to Aqaba and then turned north to run along the Rift Valley through Al-Karak to Madaba, Amman, Jerash and onto Damascus and beyond. On my subsequent Tour of Turkey, I would learn of trade via chariots between the Hittites, whose kingdom was centred in Boğazkale in today’s Turkey, and Rameses II of Egypt; and the meeting of their kingdoms at Kadesh (in today’s Syria), with the Treaty of Kadesh setting the border. All this would have been along the King’s Highway. Travelling the King’s Highway today is, of course, a very different experience to bygone eras. There’s a bitumen road to follow. In days long past, there would have been a series of goat tracks changing their precarious way through the mountains and valleys to accommodate floods, landslides and hostile tribes.

I had assumed that retracing ancient journeys would be part of my tour south. However, the driver had other ideas. His preference was to take the new super Desert Highway. We negotiated and compromised. We would take the King’s Highway to Al-Karak (Karak Castle); and then revert to the Desert Highway before turning back to the King’s Highway to Petra. We would return to Amman on the Desert Highway. And so we did. Not too far into the King’s Highway from Madaba, we first went through some fertile plains before plunging into what many tourist books call Jordan’s Grand Canyon – a deep canyon gouged by millennia of raging torrents heading for the Dead Sea. Some unimaginable millennia ago, the valley itself was part of a sea, evidenced by an abundance of sea-life fossils. You could buy pieces of such fossils at any of the look-out points along the way. For miles, the narrow road of the King’s Highway snakes down the canyon walls through several switch-backs to the very bottom, crosses a dam wall which stores a mass of water from running away to the salt-infused Dead Sea, then traces a similar pattern up the other side and finally onto the high flats. After emerging from the valley, we passed several historically significant but visually uninspiring ruins until we got to Karak. Karak Castle

My introduction to Karak Castle – and subsequent interest in it – stemmed from the movie The Kingdom of Heaven, which depicted a segment of time from a long and tortuous period of East/West history. The movie is set in the period between the second and third crusades and seeks to capture the politics of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem leading up to the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, in which Salahuddin defeated the crusader armies and later re-took Jerusalem. There seem to be lots of historical deficiencies in the movie but it features Karak Castle as the location of a (fictional, I think) meeting between King Baldwin and Salahuddin. The arch-villain of the movie, the manipulative and treacherous Reynald de Châtillon took possession of Karak Castle and made it his base for essentially defying the truce with Salahuddin. Salahuddin laid siege to Karak more than once, eventually succeeding in capturing it after his victory at Hattin where he had executed Reynald. A fictional account of one of the sieges was depicted in the movie. (I should say that the movie was filmed in Morocco, so the real Karak wasn’t in the movie.) There was a time – at the height of the power of Karak Castle – when the city was entirely within its walls, but most of the city is now sprawled over a large surrounding area. The castle and most of the city are perched on a high triangular ridge, with the main part of the castle at its apex. A dry ditch separates the bastion part of the castle from the old city that had been within its walls. Most of the city walls have been quarried over the years to build houses and other buildings.

Having read a first hand of the experience of a siege of Karak, you could feel and hear the siege as you crept along sometimes totally darkened passage ways deep in the bowels of the castle (I took the advice of a guide book and brought along a torch). Looking through the arrow-shooting and oil-pouring slits in the battlements, it seemed to be hundreds of metres to the steeply inclined ground below which dropped further into the valley. I wondered from what direction did Salahuddin come and how did his siege engines reach the battlements? In the Kingdom of Heaven depiction of a siege of Karak, all the surrounding ground was flat – quite different from the reality of Karak. A short distance from the central section of the castle, there was a smaller part whose chambers had been converted into a museum. Having visited it, one of the elderly keepers invited me to follow him across a courtyard surrounded by a high stone wall whose arrow slits provided a panoramic view down the Karak Valley to the Dead Sea. As I gazed down the valley, I suddenly remembered reading that it was in this same valley, closer to the Dead Sea, that Sodom and Gomorrah were thought to have been located. On the other side of the courtyard was a rock building with a large padlocked door. Ho opened it and we ventured down a flight of stairs into a network of chambers, the main one of which was the length of a football stadium – or so it seemed – with a rough-hewn vaulted ceiling. It was described alternatively as a meeting hall or banquet hall. It was confrontingly huge and located well below even the lower level of the castle. I thought this was something special. It’s likely not on the regular tours but it was suggested in someone’s write-up that you should ask to be taken there. Shawbak Castle From Karak, we turned off the King’s Highway and travelled along the wider Desert Highway to the turn-off to Petra (or, more accurately, the town of Wadi Musa). This took us first to the town of Ash Shawbak and the unexpected visit to ‘Shawbak Crusader Fortress’.

My guide book said that this fortress “is probably the most spectacular of Jordan’s crusader castles.” I wasn’t convinced of this, having just visited Karak Castle, but the lack of any other edifices in the vicinity certainly gave you a clear view of the of exact perimeter, shape and structure of the castle, although given its state of disrepair, the structure was evident only in a broad sense. Shawbak Crusader Fortress is perched on top of an almost symmetrically moulded hill of rocks and sparse ground cover, exactly as it would have in the 12th century. Nothing of the surrounds would have changed much. Its position on top of such a well-defined hill was the key to its being such a spectacular example of a crusader castle. It sat there like a toupee on a bald head. Its walls hugged the perimeter around the summit at a distance from the rounded peak to allow sufficient space within the walls to house its garrison and whatever other occupants it supported and safeguarded.

The castle was built by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem but became part of the “Lordship of Oultre Jourdain” centred on Karak and so also came under Reynald de Châtillon, who used it to attack rich caravans that previously passed unharmed. Salahuddin laid siege to the castle several times before finally taking it. Its location on top of a steeply sloped hill had prevented Salahuddin from using his siege engines. As with Karak, the castle was later captured and re-built by Mameluks.

The city is very spread out, with parts on a flat plain area and many key sections on surrounding mountains, on the top of high cliffs and along gorges. The first day was the quieter one. I was with a guide and group and followed the agenda with them. On the second day, I was alone and covered some 14kms on foot over every imaginable type of terrain. With the three enormous hill climbs involved, I reckoned I had done the equivalent of the Blue Mountains (Katoomba NSW) Giant Staircase about three times.

While settlements around Petra can be traced back to more than 1,000 years BC, the city complex of Petra itself dates from around the 5th century BC when the Nabataeans, an industrious Arab people, moved into the area and constructed their capital there. They controlled a network of trade and commerce reaching to Africa, India and China. It came under Roman rule around 100AD and fell into decline owing to changing trade routes. It became, in effect, a lost city until a Swiss traveller rediscovered it in 1812. It was a 2-minute walk from my hotel to the visitors’ centre and entrance to the Petra site. Fortunately, because the guide had to come and fetch me since I mistakenly thought we were meeting a half hour later. The relatively small group I was joining were kind in their forbearance.

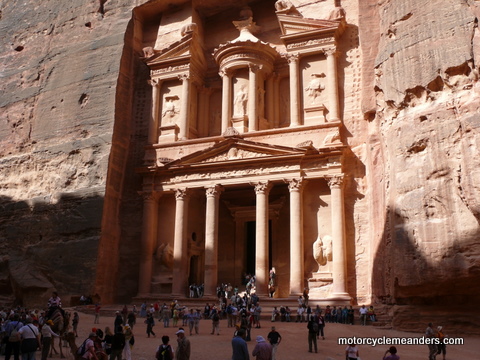

Once through the entrance gate, the first part of the walk to Petra is along a sandy, rocky path of almost a kilometre to the beginning of the Siq (Al-Siq) – a narrow gorge that winds its way 1.2km through rock walls hundreds of metres high until it delivers you to the Khazneh. Actually, our group made this first part of the journey on horseback. That was obviously just part of the deal! The Siq is a totally natural formation, although the Nabateans had widened it in parts. Apart from the towering walls, which blotted out the sun in sections, there was also the fascinating demonstration of the Nabateans’ remarkable skill for hydraulics. All along the sides of the walls were a trough (on one side) and the remnants of clay piping (on the other side) – both of which were used to carry water to the city. As the Siq approaches its end, it narrows to become almost impenetrable in terms of forward vision, thus teasing the viewer with glimpses of what lies ahead until the full view of the Khazneh emerges in stunning brilliance.

Al-Khazneh (The Treasury)

If you’re an Indiana Jones fan, this is probably the time to break the bad news that there isn’t any Holy Grail inside the Khazneh. No ancient Knight from the crusades. No labyrinths or booby traps. In fact, there isn’t anything apart from a single chamber on the other side of the entrance. The whole monument is a façade. On my first day there, I had to contend with large numbers of tourists, but arriving an hour earlier on the second day, I had the Khazneh pretty much to myself. Over the two days, I managed to see it in various lights and from different vantage points, including from the high cliffs above.

From the area of the Khazneh, flows the Outer Siq – a much wider gorge that morphs into the Street of Façades, a thoroughfare bounded by tombs of important Nabateans carved out from the rock cliffs. At the end of the street, off to the left, is what looks like a Roman Theatre – and it is in design, except that it was built by the Nabateans, but after the Romans had taken control of Petra. Unlike most Roman theatres, this one is carved into the solid rock, providing another example of the knack the Nabateans had for working with solid rock faces. Beyond the Street of Façades, off to the right against high cliff walls are the Royal Tombs. Some are particularly ornate, although erosion seems to have taken hold in many places. The largest, called the Urn Tomb, was altered in the 5th century AD to convert it into a Byzantine church. It was quite a climb to get access to the tombs, particularly the Urn Tomb. Most of the detailed exploring had to be done on Day 2, as the Day 1 tour was more of an overview. But that worked well. Main Street

The areas that once housed great temples still impress immensely despite there not being a lot of superstructure except in some places. I found myself sitting and trying to comprehend the enormity of the structures that once existed and the bustling life that must have thrived in and around this main street area.

A High Place of Sacrifice

Quite near the High Place of Sacrifice was another mound of crumbling rock that supported a brick wall of sorts and a few other decaying structures. It was scary getting to it. I recorded at the time that they were probably the remains of some crusader outpost. There was a crusader castle definitely marked on a map but it was on another ridge. Later I came across references to the mysterious structures being houses for the priests. I haven’t tried to resolve the issue. I rather fancied the crusader option. The outpost, if it were such, would have been cold, bleak, lonely, with no easy access to sustenance, but with great views all round of any and every route that armies would have had to take to pass by.

More Mountains T One last comment: on every mountain top, in addition to the special attractions mentioned, there were often large cisterns carved into the solid rock – all part of the Nabateans’ elaborate and efficient water management systems. Jerash

I was offered a guide, which seemingly was already included in the package, but declined for this tour. Sometimes they are very useful and helpful, but often enough they can talk at you with detail you don’t need to know and won’t retain beyond the visit. The alternative, of course, does require a lot more research and effort on my part; and I wasn’t as well equipped for Jerash as I had been for the other stops in Jordan. But I still figured I had enough to appreciate the magnificence and wonder of the city; and appreciate its days of grandeur.

The hippodrome looked splendid with its sandy surface, looking more like a contemporary speedway than a horse racing course. But it was mostly a forum for chariot races and gladiator fights. In fact, there were shows of such events to watch but I gave that a miss, assuming that they would have provided as much reality as the jousting demonstrations that turn up at school fêtes and country festivals. A particular treat was the incongruity of a Jordanian Pipes and Drums band in one of the Roman theatres – obviously a legacy of the days of the British Mandate over Jordan. It did provide a revealing demonstration of the acoustics of a Roman theatre, the sound being equally clear at ground level as in the very top stalls. You can enjoy their performance in the video clips below.

Photo Album Video Clips These are priceless! The subject matter rather than the camera operator, that is. Can you imagine a Jordanian army Pipes and Drums performing in an ancient Roman theatre in one of the two best preserved Roman towns outside Italy? Well, you don’t have to imagine. This is Jerash. And the Pipes and Drums are an incongruous vestige of the British Mandate of Palestine. Note the acoustics from the stage to the back stalls: a good example of Roman theatre technology.

Return to top Go to Non-Motorcycle Meanders |