|

|

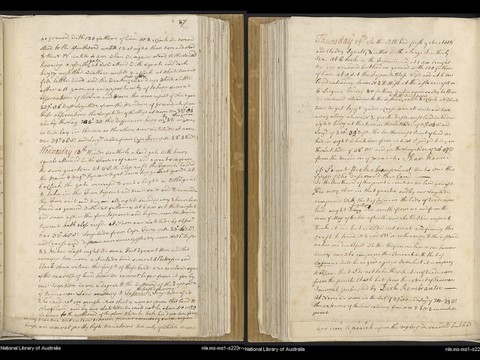

Voyage on HMB Endeavour Sydney to Botany Bay 25-29 April 2010

H HMB? Well, in James Cook’s time it stood for His Majesty’s Bark. Cook actually referred to it as His Britannick Majesty’s Bark! But you can read all about a bark (not to be confused with a barque) and about the Endeavour on the Endeavour Replica site. My initial interest in undertaking the voyage was to experience life at sea on a tall sailing ship as part of understanding and relating to the vicissitudes of an early immigrant making the voyage to Australia. It was another page in the life of my great grandfather, William Crick, along with my interest if following his Old Mail Routes. The Bark Endeavour was almost a hundred years earlier than the Barque Sibella, on which he and his brother Thomas emigrated, but it would be as close as I could get to going to sea on a vessel of a similar ilk.

The anticipation and interest in undertaking the Endeavour voyage expanded by the day, interrupted only by my desperation to recover from a foot injury incurred during my Old Mail Routes trip. Fortuitously, I was able to transfer from my originally booked Broken Bay voyage, on which I would have had to pose as Long John Silver, to the following week’s Jervis Bay voyage, giving me more time to convert my hobble to a well-disguised limpless amble. Equally fortuitously, I was able to spend a further week in recovery mode by transferring to the following week’s Botany Bay voyage. Maybe it was the transit of Venus that worked for me, as the Botany Bay voyage, on the reliable first-hand evidence of an inveterate repeat offender, was the best of the three! (Neil’s prime criteria were lots of wind in the sails and lots of swells on the sea. We scored highly on both.)

On other trips, I’ve kept a daily or intermittent blog during the trip; and then transformed it into a story page. With this trip, I kept up a pre-voyage blog for a couple of weeks as I changed plans from one voyage to the next; then resorted to Twitter for a few very intermittent reports as the voyage took place. It just wasn’t practicable to keep up a detailed blog at sea. The upshot is that this page covers the voyage itself. The pre-voyage blog, however, which contains information about Cook’s voyage on the corresponding days of April 1770 – and a little more besides – I have preserved in its original form, which you can access or download in PDF format: Pre-Voyage Blog

Reporting for Duty This is not a leisure cruise, it is hard work. Voyage crew must be able to climb aloft (39 metres in a harness), be physically fit and not suffer chronic seasickness. Good upper body strength (for handling lines) is an advantage. Thus warns the Endeavour High Seas Adventure page.

Sailing day finally came around. The Plymouth atmosphere was perfect as the grey, bleak and cool morning highlighted the lone would-be sailors almost reluctantly trudging along the harbour-side promenade wet from the night’s rain. The converging point was HMB Endeavour, its tall, line-laden masts starkly brought into focus by the pitch-black netted rigging ascending from the deck to the tops of the three masts. The sight of Endeavour, waiting patiently for its new crew to grapple with its complexities, was exciting, alluring and foreboding. The excitement began to dominate as we filed past the first mate (not that we knew he was the first mate at that stage) to be “signed on” for our contracts of service to His or Her Majesty – depending on your time-frame of choice. We were ushered into three “watches” each centred on and named for one of the three masts: Foremast Watch, Mainmast Watch and Mizenmast Watch (the mizenmast is the rear-most mast). These Watches (I’ll use a capital M for them from here on) were, in effect, teams with specific responsibilities relating to their designated mast and its sails; and that work together in shifts (“watches” with a small m) to care for the ship under the tutelage and sharp eyes of the officer of the watch and the professional crew members of each Watch. The watches were four hour stints around the clock, except for two 2 hour ones at 4.00pm and 6.00pm (the “dog” watches), that ensured that no Watch got stuck with the same watch on successive days. Members of each Watch pretty much ate, slept and laboured together. Our First Encounters with Endeavour

On reaching the deck, you slithered backwards through a small hatch, disappearing into the dark below like poor Alice tumbling down the white rabbit’s lair. This dropped you onto the 18th century deck, installed in the original Endeavour as part of the naval refit to convert the collier Earl of Pembroke into the scientific expeditionary HMB Endeavour. Forward of where you found your feet on the darkened humid deck were cabins occupied by professional crew members. Feeling your way astern, waiting for your pupils to dilate sufficiently to reveal the details of the expanse ahead, you encountered wooden tables suspended by ropes from the supports of the weather deck above. In Cook’s time, this area served as the crew mess hall, sleeping quarters and recreation room. As you ventured further astern, with the ceiling clearance dissolving to about a metre, you crawled, like Alice changing size, to reach an alcove providing access to the officers’ cabins, with no increase in headroom. The area between the crew’s area and the officers’ cabins was occupied in Cook’s time by 12 naval marines. The Alice-like alcove and cabins combined with a heighten quarter deck up top to provided room for a mezzanine deck between the 18th century deck and the weather deck. Herein was housed the supernumeraries’ cabins and the Great Cabin.

In Cook’s day, this same area was home for twice our number. The hammock is an old naval tradition dating back to the 1500s. It turned out to be quite comfortable even though it was impossible to turn in it. Its canvas sides encased you in a way that no amount of rolling of the ship was about to toss you out or even disturb your equilibrium. As the ship rolled, all the hammocks swayed back and forth – always in unison and always balanced; not unlike the mountings of the helm compass which kept it level despite the pitching and rolling of the deck. By day, our hammocks were wrapped and stowed, magically transforming the dormitory into a mess and recreations area. Amongst the ship’s complement, were four supernumeraries – so called. The invitation to join as a supernumerary was decidedly more enticing than for voyage crew:

I originally thought the descriptor of supernumerary was either pretentious or derogatory or even both, but I was relieved and even delighted to discover that it was the same term used in Cook’s day to describe his scientific ensemble led by Joseph Banks. Their roles and functions were the very raison d’être for the original Endeavour voyage. Cook even deferred to them by giving up his cabin to Banks; and the officers’ cabins to the other supernumeraries. The Great Cabin became the operations room for the scientific expedition, depriving the officers of their normally expected privilege or perk of wining and dining in style. (In the circumstances, I’m not so sure Cook would have got much opportunity to relax in the Great Cabin.) Our four supernumeraries occupied the cabins of the original supernumeraries. The captain occupied the cabin Cook relegated himself to. For us voyage crew, however, unlike Cook’s crew, there was also the next level down – the 20th century deck. Here we found a modern galley, dining area, male and female change rooms, spacious-enough wash rooms, showers and the ship’s heads, a quaint ship-term for toilets, although their peculiar nomenclature served to differentiate them from a traditionally operating cistern which does not require multiple pumping or manual refilling processes.

It was sobering to watch the grand structure of the Sydney Harbour Bridge fill your windscreen of vision and then smother the whole ship as it passed underneath. As we passed by Sydney Harbour’s renowned landmarks of the Opera House and Fort Denison, built to resist Russian invaders at the time of the Crimean War, we became more conscious of the decking structure of Endeavour. In the middle of the ship, a flat, level deck was designated the waist of the ship. Up front, was the fore deck, slightly raised, which housed the foremast, the base of the bowsprit, the spar that reaches far out front of the bow and supports the two sprit sails, and the gigantic ropes of the anchors. At the stern was the quarter deck, raised more prominently from the waist and sloping upwards to the stern, thus providing the head room for the Great Cabin below it.

Our Foremast Watch, which included throughout the voyage the supernumerary occupying Daniel Solander’s cabin, came up first for the “up and over” training. This involved scaling the rigging from one side of the ship to the “top” (which we called “the shooting top”) high up the mast and then down the other side. My main concern all along had been whether my tightly strapped foot, strained in a couple of places by being tossed off my F800GS in pursuit of Old Mail Routes along the Murray River, would cope with climbing on the thin ropes of the rigging. This would be the first serious test. The combination of the physiotherapist’s strapping technique and a thickly soled hiking shoe thankfully dispersed the pressure of the ratlines to infinity. Like most people, I had a fairly good picture in my mind of a sailing ship’s rigging: the vertical thick black ropes running from the ship’s railing and converging as they reach the top of the first stage of the mast, be it the fore, main or mizen mast; and the thinner horizontal lines running between them. The former, I learned, are the shrouds. The thinner horizontal lines between the shrouds are the ratlines, which sailors, typically dropping syllables, call rattl’ns. Scaling the rigging, I always thought, would be the pinnacle of challenge and accomplishment of the voyage. The image of sailors, naval, merchant or pirates, scrambling up the rigging must be etched in anyone’s mind who has watched sea-faring movies from the time of Errol Flynn to Johnny Depp and Russell Crowe. So I knew what we were in for. Or so I thought.

Imagine climbing the rigging. You hang onto the shrouds, you put your feet on the rattl’ns; and up you go, hand over hand, foot after foot. It wasn’t nearly as difficult or scary as I had thought. But I hadn’t counted on the futtocks. As the shrouds and rattl’ns converge onto the top of the first section of the mast, a platform (the ‘shooting top’) protrudes. It provides a load-carrying anchor for the upper shrouds that support the next section of the mast. The ‘problem’ was that the platform stopped your climb metres short of the convergence point of the shrouds. This is where the futtock shrouds take over. They provide a link between the main shrouds and the edge of the platform carrying the load of the next lot of shrouds. They are the access to the platform and the upper shrouds. Transferring to the futtocks, however, means you are now hanging out rather than leaning in. The last metres are climbed with every arm and shoulder muscle straining to keep you as closely hugging the rigging as you can, as gravity wants to pull you down. “Don’t pull with your arms. Just hang on. Do all the pushing with your legs.” That was the counsel of the professional crew. I had no idea what I was pulling or pushing with. I was just clinging tightly to whatever I could grasp and carefully edging a foot to the next rattl’n. The rattl’ns seem to run out far too short of the edge of the platform, which you see only if you angle your head back at a point of near neck-dislocation. You then feel gropingly for some point of contact around and over the edge. The next lot of shrouds heading upwards come into reach. You can’t get your hand around the three strands that start the shrouds, so you grapple to clutch a single strand – not easily. The ‘leap of faith’ at this point is to let go with one hand – as you must do – to reach a higher holding point. The golden rule, we were told, was “three points of contact.” That was easy enough coming up the main shrouds when you were leaning in. When you’re leaning out, it’s easier said than done. When you’re leaning out and reaching out and around, feeling for an out-of-sight holding point, it’s even more of a challenge! But you find a point of contact and pull yourself up enough to get a knee on the edge of the platform. From there, you’re home. The reward was amazing. Standing on the ‘top’ or the “shooting top” (where sharp shooters were placed in an altercation) was breath-taking. It was such an achievement. It was ground-breaking. It was almost unbelievable. Little did I know there were greater challenges to come! There was a lot more, important but less nerve-racking, training to be had: helming – we would all have to steer the ship in various sea conditions(how do you keep a cumbersome, slow-responsive 18th century bark on a compass course or on a “full and by” course, reading the wind on the sails); the basics of hauling and easing on the yards as the ship turns into or away from the wind; the baffling and mind-boggling array of lines, each neatly coiled along the deck and each with its name and function; the allocation and execution of duties when you’re called to “bracing stations”; the techniques of unfurling and furling the sails; and many more tasks, few of which were understood, let alone remembered; but delivered when it counted. Setting Sail

The first night was our introduction to dozing lazily in our hammocks, while always conscious of the noise and movement of Watches and watches coming and going, bumping into your hammock and audibly apologising, thus ensuring you woke up even if the movement and noise hadn’t woken you. The morning came and the rising sun raced unimpeded to the Harbour Bridge and Opera House. Pancakes for breakfast lulled us momentarily into a false sense of assurance that we were on a pleasure cruise. Then we became aware of the professional crew stringing out safety lines criss-crossing the decks. Murmurings among the professional crew revealed that this had not happened on any of the previous voyages and queried why now! Well, the captain knew best; and, indeed, he did, as we were to discover. As Foremast Watch, we were, now “for real” clambering up the rigging and over the dreaded futtock shrouds to unfurl the sails. I was a bit tardy in getting onto the rigging and so ended up watching the unfurling from the shooting top. That was fine. It was challenging enough at that stage to have conquered the futtocks a second time without having to venture onto the yards. That would come later with a vengeance. With favourable winds, now blowing from the south-east, we were able to make our way down the harbour and out through the heads under sail, with the motor idling to conform to regulations. It was a great sight to be on deck in this anachronistic vessel sliding under billowing sails towards a narrow, one nautical mile-wide escape to the unimpeded open seas. Then, the starboard turn to East and only the horizon in front. Goodbye, Sydney Town! The Open Sea

“One hand for you; one hand for the ship” was the adage of the day. Clinging – mostly with both hands for the ship – to the starboard railing and safety ropes, you would drop as the ship slid down the side of a passing wave into a trough of royal blue water, watching with some awe as the outside wall of the trough blotted out the sky then suddenly descended on the ship, which, in a quick response, would cunningly raise its side to let the wall pass underneath; and in doing so lift you high above the now sinking port side. Then the process would happen again....and again.

This wasn’t quite rounding the Horn; but then again, it could be anything or anywhere you wanted it to be. The moments were yours. Your communication was internal. You simply held on and let your senses and imagination take over. And you could be anyone you wanted to be: Ulysses, Jason of the Argonauts, Peter Pan, Horatio Hornblower, Captain Jack Sparrow, Jack Aubrey or, more pertinently, Lt James Cook. The list was endless. Evening Abatement As evening approached, the opposing forces of ship and sea drew back to their lines. The wind eased but continued to fill the sails. The rolls and pitching abated to a steady drone. We swayed the night away in our hammocks with occasional surges in pendulum pace.

The weather deck, thankfully, is filled with the impending full moon. It might have been totally dark. No lights allowed as they interfere with night vision. There are tasks to accomplish, checks every hour around the whole ship, and time to be hypnotised by the glittering phosphorescence darting around the bow of the ship as it shatters the moonlit surface. It gets colder as the moon disappears behind cloud and eventually sinks long before the sun starts to emerge from below the horizon as though it also had to find holds to pull itself off the futtock shrouds over the edge of the shooting top. The sea lights up, the sails takes on a golden hew, the new day already augurs a calmer sea and smoother sail. While the day was breaking, our Watch gets called to ‘bracing stations’. We’re about to wear ship. That’s a manoeuvre that has us change tack by turning against the wind rather than into it; and coming right around to the opposite tack. Endeavour doesn’t much like tacking (i.e. changing tack by turning into the wind). It fusses with its head into the wind and only reluctantly lets it happen. It gets tetchy if you try to make it run closer than about 70 degrees into the wind. Endeavour just doesn’t do windward! Tacking is its greatest dislike; and, in any event, it’s a difficult manoeuvre requiring all hands operating in a sharply coordinated movement. It’s so much easier to wear ship even though you lose ground. While the wind retained a chill, the seas relented sufficiently for the safety lines to come down and a few of the happy buckets to be retired – but far from all! A pod of pilot whales guided us for a while before deciding we were too slow. With winds easing, the 0800-1200 watch got to set the top gallant sails – the top most square sails on Endeavour (in ship-talk, the bottom square – actually oblong – sail on a mast is the course’l. The next one up is the tops’l. And the next one after that is the t’galn’t.) The TGs (lazily called such at times) provide more power in light winds by picking up the less turbulent higher breezes without altering the centre of gravity. Like a motorbike, you don’t want too much load up high – keep the centre of gravity low – so the TGs need to come down if winds pick up, as they did later in the day. Beating North

The word filters out that we might tack. Why, given Endeavour’s likely antagonism to being made to face the wind? Well, the unanimous response was “because we can!” More likely, the motivation would have been because it’s important that the captain control Endeavour – and be seen to – rather than Endeavour control the captain. The call goes out “all hands on deck”. So much for afternoon tea that was just announced. Tacking requires everyone on deck with a role to play. Imagine the average recreational sailing boat: you have a mains’l attached to one boom that requires moving from one side to the other at that vital moment as the wind abandons one side of the sail and fills the other. It requires some skill and dexterity. Endeavour has potentially up to a dozen “booms” all of which have to be moved in unison. And these aren’t booms that swing around with the wind catching the sail. They are the yards that have to be hauled, bearing sails that have to hauled separately but in close synchronisation with their yards. One yard and its sail require about three hands to haul the yard, a couple to haul the sail and a few to ease off the lines on the opposite side to the haul. “Two, six, heave” echoes across all decks time after time as the helmsman turns Endeavour into the wind, its head wavering. Its aversion for wind in its face buckles under the demanding hand of captain and helmsman. It shys at the midpoint but comes around, its objections quickly dissipating as the new tacking angle increases away from the wind. We’ve tacked.

But then the order comes to tack again. Incredulously, ship and crew reel together at the prospect. But a second tack gets executed as effectively as the first one. An hour or so later, flushed and lulled with two successful tacks, we go for a third. However, Endeavour is ready for it this time. It fights the helmsman from the first turn of the wheel. It feigns a stall and allows itself to drift backwards. A tack isn’t going to happen. It’s aborted and we again resort to wearing ship.

Somewhere along this run I had the helm. There are always two on the helm: the brain and the brawn. The helmsman (the brain) has responsibility to keep the ship on its designated compass-course given to the new helmsman and repeated by him or her to the officer of the watch: “course two-five-zero!” The compass is at your elbow to guide you. Turning the helm can be arduous, so a second pair of hands provide additional muscle (the brawn). It was late in the afternoon. We were still struggling to stay on a north-westerly course against a wind that wanted to push us out to sea. Having taken the helm, the officer of the watch changed the compass-course order to “sail full and by!” Oh? Maybe it was my blank look that prompted him quickly to follow up with more detailed instructions: “watch the bottom corner of the main tops’l. Keep it full. Steer gradually windward. Once you see the sail starting to luff, ease to starboard to fill the sail again. Find the magical point where you the sail is always on the verge of luffing but never does!” We are steering by the wind rather than by the compass. The objective is to steer as close to the wind as possible. The wind determines the course. That added a new and challenging dimension to my time at the helm. The Run Home

We enjoy good winds and calm seas as we run down the coast for the rest of the night and most of the next day. We end up way south of the Royal National Park, with the prospect of a lot of beating against a wind shifting more westerly to reach Botany Bay. We turn and ease westward for a while before turning north-west to Botany Bay. We get to a point where we defer to Endeavour’s well-known windward animosity and decide that furling sails and engaging diesel power for the last 20 nautical miles was the only assured way of meeting the Botany Bay pilot. Our Foremast Watch is back on duty for the 1200-1600 watch (there were eight hours in their somewhere between our watches!). But this is now the “bring it home” watch. As the duty watch, our first task is to furl the tops’l on the main mast. Up the port side rigging (you always climb with the wind in your back), over the futtocks, then transferring to the next set of shrouds and rattl’ns from the outer edge of the shooting top to the t’galn’t yard. Before reaching the t’galn’y yard, you step off the rigging and onto a wire hanging below the tops’l yard. You then make your way along the foot wire, holding another wire running along the yard, until you reach the mast. Around the mast is a narrow collar – about 20cms wide – which provides a stepping path around the mast to deliver you onto the starboard side of the yard. Then a process of side-stepping along the foot wire to take up a position along the yard. The sails by now have been folded in at the bottom corners and up the middle – effected by hauling and securing the appropriate lines.

At first I was reluctant to let go the wire running along the yard. I held on with one hand and pulled at the sail with the other. It didn’t take long, however, to realise this was not very efficient; and just a little longer to conclude it was decidedly ineffective. Hesitatingly, I grabbed the sail with both hands. The weight of the sail was more than enough counterbalance to keep you in place, even when you had to lean back to shove the folds of sail down your front, provided, of course, you didn’t let go; and, as we were to be told later by an old timer “you’d be silly to let go!” With the task completed, it was back onto the rattl’ns and down...to the course yard...not even as far as the shooting top. Same process, except that the course sail is the biggest and heaviest. It didn’t help to have tied the safety strap on my harness tightly to the yard together with the sail. That took some undoing before I could manipulate lines, sail and harness to tie what had to be tied and keep apart what had to be apart. Back down on the deck, having made a last transit of the futtock shrouds, we were all pretty exhausted but thoroughly elated. Standing out on the edge of the tops’l yard, a 12 knot wind blowing your face, the ship gliding forward at about 6 knots, blue sea all around far below and as far as you can see, the outline of the cliff faces of the coast off in the distance, the only sounds the wind in your ears, a hive of silent activity over the decks below – what a magical experience! The trance is suddenly broken only by our upperyardsman shouting at you to secure the sail. Botany Bay

The last night of the voyage, quietly at anchor or securely moored, is a celebration of the achievement. A ‘gala dinner’ takes place on the 18th century deck in the crew’s mess of Cook’s day. In keeping with navy traditions, the officers wait on us humble but proud sailors, ratings, and supernumeraries. An impromptu Sods’ Opera performed by Watches and professional crew culminates in a toddy of rum toast from all – that is, an Endeavour toddy: a soup spoon! The watches continue through the night. No ship can be left unattended or uninspected. The ship’s log must continue. Records kept. On the 2000-0000 watch (broken into two halves at anchor), we record, as usual, the under-keel depth (1.2 metres – not much with low tide still three hours away); the radar sweep of 1.5 nautical miles; wind speed; and the usual run of inspection reports: fridge and freezer temperatures, bilge depth, engine room status, cisterns not overflowing, heads (toilets) all operating (knock and shout before entering the female block!), everything on deck in its place etc. It was nice to get to ‘bed’ a little after 12.00am for the rest of the night. An early breakfast on the 20th century deck or the weather deck, if you chose so, preceded a busy few hours of packing, stowing and being ferried in Endeavour’s run-about to Cook’s landing beach. This was farewell to Endeavour. The end of the voyage. Two Cultures W

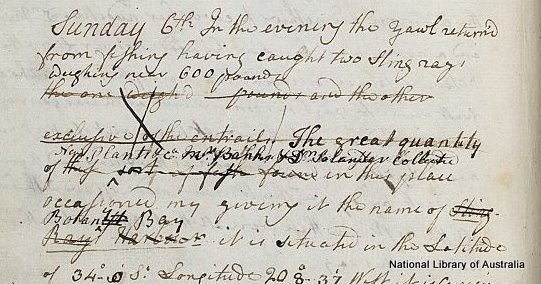

The area surrounding Cook’s landing point is now part of the Kurnell National Park. The park headquarters has a good visual display of Cook’s landing and associated events and the lives and impacts on the local inhabitants at the time. There’s a bit of indecision about the dates relating to Cook’s landing. Speakers at the ceremony, either without consultation or because of conviction, alternatively said it happened on the 28th or the 29th. Signs around the park alternated between the two dates. A national park booklet and the static displays at the park HQ categorically said the 29th (without admitting to possible ambiguity or disclosing their excising of key entries of Cook in his journal which cast light on the dates). So was it the 28th or the 29th? I have tried my hand at an answer, but you may think differently: Cook's_Landing_-_28_or_29_April.pdf

I suspect a lot of the viable answers will remain forever rooted in individual perceptions. We are and will always be a land of many cultures. History will always record the encounter of two cultures. Hopefully, each will retain its role and value. Irrespective of perceptions and impacts, the Endeavour voyage in its own right retains significance for its historical and scientific accomplishments. James Cook was first and foremost an extraordinary seafarer, navigator, cartographer and leader of men. To share in his and Endeavour’s 18th century feats by voyaging on today’s Endeavour is a privilege and a treat. To have been part of the Two Cultures ceremony was a special reminder of the bigger picture of human impacts that one historical event can trigger. Photo Album Here is a photo album of the yoyage Video Clip Here are a couple of short video clips of Day 1 at sea. The first one is a shot of the deck as Endeavour rolls and pitches. The second one was shot from a helicopter (FireAir 1) that seemed to have diverted from a training exercise to take a peek at us.

Fair winds and following seas! |